Bali Myna takes flight to Nusa Penida (Dijkman 2007)

Despite long-standing endeavours to salvage the critically endangered Bali Myna Leucopsar rothschildi from the hands of unscrupulous traders and status-conscious politicians, its numbers have dwindled in the past couple of decades to only a handful (see Birdlife International 2001).

Very recently, however, a number of these popular birds have found a new haven on the island of Nusa Penida and are breeding and producing offspring in surprisingly new ways. Besides the Bali Myna, other endemic birds profit from a successful nature conservation project as well. Thanks to this comprehensive programme, undertaken in cooperation with the island's inhabitants, both the local flora and fauna are getting a new chance of survival.

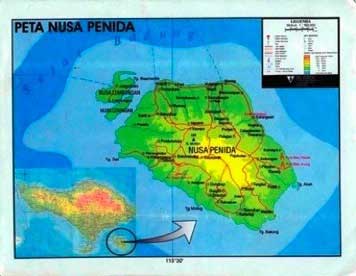

Nusa Penida

The open and mountainous landscape of Nusa Penida is surprisingly different from mainland Bali. In comparison, Nusa Penida is quiet, hot and arid. Indeed, the countryside seems to have more in common with the dry islands further east, such as Sumba and Sumbawa. No wet rice cultivation is to be found on this ‘magic island’, where the main source of sustenance is seaweed. Nusa Penida is also famous amongst the Balinese for its Hindu Temple at Ped, where people return frequently every year for a spiritual journey to experience the healing powers from the local gods. Others say that the island is home to magical forces, black magic and ill omens. The ubiquitous teak trees, with their unmistakable large leaves - evidently oblivious to the island’s reputation - thrive on this dry and infertile soil.

Up in the mountainous area of Hutan Tembeling, near the village of Batumadeg, lies a long strip of pristine forest, meandering down towards the sea where a clear stream at the bottom of a ravine trickles into a natural swimming pool. It’s the dry monsoon, and on the way up the hills, the promised Sabuluh waterfall is hardly discernible. The pool, however, is filled with crystal-clear water and a delight to swim in. Surrounded by a large school of curious gray fresh-water fish, one hardly notices the presence of more-than-curious shrimps; these small and gentle creatures seem quite unperturbed by casual waders. The trees and shrubs around the pool, next to a modestly designed white cave temple, give shelter from the hot midday sun, high above, where the canopy forms a padded blanket through which enough light filters down to observe the surroundings. The narrow path leads further down over layers of thick foliage and through dense undergrowth. Part of the trail is still used by the local farmers for their livestock, to find water half way down. Further down still, the trail descends more rapidly where apparently cows find it too unsafe to wander, ending at a pebbled beach studded with huge boulders. Suddenly, one gapes at a tumultuous ocean, with waves as high as a house, breaking violently against the steep cliff with thunderous noise. The view to the Indian Ocean is spectacular; there is a high and thin piece of land separated from the mainland to the right and in this snug bay of light the colour of the sea is enriched with every hue of blue. Wary, however, of its ominous waves, it is perhaps wise to let oneself be captivated by its beauty at a safe distance, on top of a few rocks close to the forest edge.

Up in the mountainous area of Hutan Tembeling, near the village of Batumadeg, lies a long strip of pristine forest, meandering down towards the sea where a clear stream at the bottom of a ravine trickles into a natural swimming pool. It’s the dry monsoon, and on the way up the hills, the promised Sabuluh waterfall is hardly discernible. The pool, however, is filled with crystal-clear water and a delight to swim in. Surrounded by a large school of curious gray fresh-water fish, one hardly notices the presence of more-than-curious shrimps; these small and gentle creatures seem quite unperturbed by casual waders. The trees and shrubs around the pool, next to a modestly designed white cave temple, give shelter from the hot midday sun, high above, where the canopy forms a padded blanket through which enough light filters down to observe the surroundings. The narrow path leads further down over layers of thick foliage and through dense undergrowth. Part of the trail is still used by the local farmers for their livestock, to find water half way down. Further down still, the trail descends more rapidly where apparently cows find it too unsafe to wander, ending at a pebbled beach studded with huge boulders. Suddenly, one gapes at a tumultuous ocean, with waves as high as a house, breaking violently against the steep cliff with thunderous noise. The view to the Indian Ocean is spectacular; there is a high and thin piece of land separated from the mainland to the right and in this snug bay of light the colour of the sea is enriched with every hue of blue. Wary, however, of its ominous waves, it is perhaps wise to let oneself be captivated by its beauty at a safe distance, on top of a few rocks close to the forest edge.

Image left: Djuna Ivereigh (2007)

Bayu Wirayudha, Balinese initiator of this nature conservation project, with grains of blessed rice on his forehead is radiant and all smiles. He has reasons to be truly proud, for he has been running the Nusa Penida Bird Sanctuary (NPBS) since May 2004, and is working alongside the local population to enhance their chances of a better life. He is, in fact, a bit of a busybody 'millipede'. Apart from running the Bird Sanctuary, he is also a veterinarian, founder & director of Friends of the National Parks Foundation and director of Begawan Giri Foundation's Environment Division. He reckons that close cooperation with the local population is indeed the only way to guarantee the survival of the newly introduced fabled symbol of Balinese fauna. This gorgeous bird, in Indonesian 'Jalak Bali', with its tufted white crest, snow-white plumage and black wing- and tail-tips sports a pair of blue spectacles in truly magnificent fashion. Apart from its illustrious physical beauty, its endearing behaviour and chirpy voice have made this mynah one of the most sought-after birds in all of the Indonesian archipelago, leading to its near extinction (it was only placed on CITES Appendix I on 1 July 1975). The natural habitat of the Bali Myna is not Nusa Penida, but the West Bali National Park where as few as five birds survive today. The conditions there are far from ideal, despite numerous costly national and international programmes to protect this bird and to monitor its breeding in the wild. Negligent wildlife management, illegal hunting and dubious political games seem to have caused the current dire state of affairs.

Breeding and release

On 10 July 2006, 25 Bali Starlings were released at various locations in Nusa Penida. These birds are the result of a non-commercial breeding project initiated by the Begawan Giri Foundation and the Friends of National Parks Foundation (FNPF). The in-situs breeding of the Bali Starling has been the main activity of the Begawan Giri Foundation since 1999, the year of its inception. Various measures have been taken to ensure the success of this release programme. The most striking of all, perhaps, is the fact that an overall agreement was reached by mid 2005 between the 35 villages on the island, the two foundations and the Balinese state authorities involved in nature conservation. To guarantee the safety and survival of the birds, prior to the release date, the birds were ‘offered’ to the gods by means of a series of religious ceremonies performed by Hindu priests. This way, the gods were asked to give protection to the birds after their release since they no longer are the possession of humans, but are entrusted into the hands of the divine. Secondly, traditional Balinese law (Awig-awig) provides a good basis for their protection as well. This law has a strong foothold within rural Balinese society and sanctions have been seen to deter potential illegal bird catchers. Alongside religious and social protection, the Bali Starling enjoys the co-operation from the port authorities, part of the formal Indonesian Legal System on the island, who agreed to keep a close watch on illegal trafficking and bird trade.

Community development and reforestation

As part of an integrated approach to ensure the survival of the Bali Myna in the wild, a large section of the Nusa Penida Bird Sanctuary at Ped has been made available for reforestation purposes. The FNPF has been nursing around 50,000 young plants which are being grown and prepared for distribution all over the island at the onset of the rainy season in December. Together with the population on the island, a number of trees have been selected for future use by the people themselves, such as teak Tectona grandis, mahogany Swietenia mahagoni, sugarpalm Arenga pinnata and an especially strong bamboo variation named Guadua BambooGuadua angustifolia to be imported from Colombia, South-America. This bamboo species is considered the strongest in the world and provides excellent construction material. People can grow these for production in order to generate income. Apart from these, it is expected that the introduction of jatropha trees Jatropha curcas, an alternative source for biodiesel, will contribute towards better sustenance for the locals. Of course, together with other plant species, two other objectives are achieved: reforestation of particularly arid and vulnerable areas and a source of food for the birds. The “delundung” Erythrina lithosperma, a sacred tree of the same family as the bright red flowering Coral Tree, will harbour large quantities of insects and provide ample nesting space. Other examples from a long list of trees and plants to be distributed amongst the local population of Nusa Penida are the various ficus subspecies including the sacred ‘beringin’Ficus benjamina.

As part of an integrated approach to ensure the survival of the Bali Myna in the wild, a large section of the Nusa Penida Bird Sanctuary at Ped has been made available for reforestation purposes. The FNPF has been nursing around 50,000 young plants which are being grown and prepared for distribution all over the island at the onset of the rainy season in December. Together with the population on the island, a number of trees have been selected for future use by the people themselves, such as teak Tectona grandis, mahogany Swietenia mahagoni, sugarpalm Arenga pinnata and an especially strong bamboo variation named Guadua BambooGuadua angustifolia to be imported from Colombia, South-America. This bamboo species is considered the strongest in the world and provides excellent construction material. People can grow these for production in order to generate income. Apart from these, it is expected that the introduction of jatropha trees Jatropha curcas, an alternative source for biodiesel, will contribute towards better sustenance for the locals. Of course, together with other plant species, two other objectives are achieved: reforestation of particularly arid and vulnerable areas and a source of food for the birds. The “delundung” Erythrina lithosperma, a sacred tree of the same family as the bright red flowering Coral Tree, will harbour large quantities of insects and provide ample nesting space. Other examples from a long list of trees and plants to be distributed amongst the local population of Nusa Penida are the various ficus subspecies including the sacred ‘beringin’Ficus benjamina.

A project of this size could not have been a success without additional support activities such as educational programmes, both in-house and at schools around the island, and general promotion amongst the local population. Special youth clubs have been formed to organize trips into the interior, where birding contests are held, and awareness is raised on the preservation of our natural environment. All of these and many more activities will be continuously staged by some nine permanent and a handful of freelance staff members who are only willing to call their project a success if more than 100 Bali Mynas are freely flying around the island. The project enjoys financial support from the Gibbon Foundation Indonesia.

A project of this size could not have been a success without additional support activities such as educational programmes, both in-house and at schools around the island, and general promotion amongst the local population. Special youth clubs have been formed to organize trips into the interior, where birding contests are held, and awareness is raised on the preservation of our natural environment. All of these and many more activities will be continuously staged by some nine permanent and a handful of freelance staff members who are only willing to call their project a success if more than 100 Bali Mynas are freely flying around the island. The project enjoys financial support from the Gibbon Foundation Indonesia.

Presently, the released Bali Mynas are breeding and producing offspring in their newly adopted natural habitat. The survival rate of the released birds is high, with – until the time of writing - only one death amongst 25 birds. Oddly, however, and seemingly in contradiction with what

was known of their natural behaviour in the wild, they seem to be adapting quickly and finding alternative nesting places. Most studies have it that the Bali Myna only nests in pre-formed tree-holes, ones left for example by barbets and woodpeckers. One pair of Bali Mynas in Nusa Penida, however, has chosen an ordinary coconut tree, another pair has found its home in a sugar-palm and two pairs are seen to have established themselves in one and the same ‘punga-punga’ tree Ficus sp. near the village of Saren (Batumadeg). The pair nesting in the sugar-palm has raised two chicks that are (at time of writing) ready to leave their home, and have been observed making their first attempts to get airborne. In total, two pairs have successfully produced offspring. Other nesting sites used by the Myna are beehives and artificial nest boxes attached to fig trees. This alternative breeding behaviour is unique, since apparently they have shifted away from their supposed territorial habits, and have accepted entirely different conditions for their offspring. In fact, the Balinese are delighted to find one pair investigating the niches of a Hindu temple, also at the village of Saren, in search of a suitable nesting place. Unfortunately, no offspring has been raised here so far. The local community, however, has shown its commitment in protecting the released birds and has joined the team of conservationists in their continuous efforts to monitor them. The conservation team believes, therefore, that the island of Nusa Penida has proved a suitable area for the Bali Myna release programme.

BirdingAt Nusa Penida, there are interesting possibilities for birding excursions. Apart from the Bali Myna, you’re likely to see the endangered Yellow-crested Cockatoo (Cacatua sulphurea parvula),hordes of Sooty-headed (Bulbul Pycnonotus aurigaster), and raptors amongst which the Brahminy kite (Haliastur indus). Once you reach the top of the area around Tembeling Forest (Desa Batumadeg), you will be able to observe the Bali Myna (and their young chicks!) from a cool and sheltered birding post, close to one of the large enclosures from which the birds are reintroduced into their new surroundings. The latest bird to be introduced on the island is the Java Sparrow Padda oryzivora, which was released in September as it is another of the endangered bird species in Indonesia.

Future prospects

The future has much in store for the island. It is expected that with the success of this breeding, reforestation and community development project, ecotourism will stand a real chance on the island. Bayu is considering the possibility for a camp site up in the mountains, hiking and birding trails. This will further benefit the local economy and general development of the island.

There are several other very important bird species presently to be found on Nusa Penida, and one of these is the endangered Black-winged Starling Sturnus melanopterus. The island is the only location where it is known for sure that the species survives in the wild. Ironically, the bird was introduced to Nusa Penida in 1986 by President Soeharto when he officially opened the water catchment basins on the island; apparently, the birds were released from a helicopter! At present it is still a rare sight but it is on the rise, since it too profits from awig-awig law discussed above. Unfortunately, no recent survey has been organised to estimate the size of the population, but the NPBS is gathering information.

Based on casual observations, Bali Mynas and Black-winged Starlings do not seem to interact significantly on Nusa Penida and are not considered competitors for food or nesting sites. Food here is abundant for both species and they appear to live together side by side peacefully except for one occasion where paired-up Bali Mynas were seen to chase Black-winged Starlings from their territory. Much like the Bali Myna, the Black-winged Starling has chosen alternative sites and instead of using tree-holes it now finds nesting spaces virtually anywhere, including holes in limestone cliffs.

Reports from villagers and farmers indicate that the Black-winged Starling is to be found around Wates (the remote south-east corner of Nusa Penida), Sedihing (where three Yellow-crested Cockatoos live, south-east), Guyangan, Saren (at the release site of the Bali Myna, Tembeling forest, south-west), around Banah Point (magnificent cliffs, south-west), and Nusa Ceningan (the smaller sibling of Nusa Penida to the north-west).

Apart from the breeding programme for the Bali Myna, a similar integrated breeding project was set up for the Mitchell’s Lorikeet (Trichoglossus haematodus mitchelli) about a year ago. This bird, like the Bali Myna, is a native to Bali but disappeared there in 1988. Sadly, no efforts have been made to red-list the lorikeet for official protection. At present, there are 35 lorikeets in captivity at the Nusa Penida Bird Sanctuary and they too may be hugely important for the survival of the three plain red-breasted, indigo-bellied subspecies of the westernmost end of the lorikeet’s range. Consideration is being given to the release of some of these birds on Nusa Penida in the future.

Last but not least of the endangered bird species, a few Yellow-crested cockatoos still live on the island. Their numbers have decreased sharply since 1965, owing to trapping, loss of habitat and nesting locations. One pair lives in a gigantic sacred “stinky sterculia” Sterculia foetida in Karanggede, not far from the Bali Myna release locality, and have chosen a hole in this tree right underneath the nest of a pair of Brahminy Kites. Not a very favourable location, one could argue… but perhaps here as well, very much like the Bali Myna itself, the birds feel protected by the local deities, since this majestic tree stands on the grounds of a beautifully located temple, on the edge of a steep cliff, with a view to an indigo-blue ocean that is situated between Bali and this enchanting island of Nusa Penida.

References- BirdLife International (2001) Threatened birds of Asia: the BirdLife International Red Data Book. Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International p.2375-2391

- FNPF & Begawan Giri Foundation, Pelepasliaran dan Perlindungan Burung di Kepulauan Nusa

- Penida, Nusa Penida Bird Sanctuary Activity Report, April–June 2006 (unpublished)

- MacKinnon, J., Field Guide to the Birds of Java and Bali, Gadjah Mada University Press, 1991

- Ruggles, A., Lories & Lorikeets, The brush-tongued parrots & their care in aviculture, Blandford London 1995

- Sugiarta, M. interviews (veterinarian & site manager at Nusa Penida Bird Sanctuary), July-December 2006, Nusa Penida & Bali (Indonesia)

- Sujatnika et al, Indonesia, Conserving Biodiversity: The endemic bird area approach, PHPA/Birdlife International-Indonesia Programme, Bogor 1995

- Setiawan, I., The Status of Cacatua sulphurea parvula on Nusa Penida, Bali and Sumbawa West Nusa Tenggara, PHPA/Birdlife International-Indonesia Programme Laporan no.6, 1996

- Wirayudha, I Gede Nyoman Bayu, interviews, July-December 2006, Nusa Penida & Bali (Indonesia)

- Wirayudha, I Gede Nyoman Bayu et al, Post Release Progress Report of Bali Myna (Leucopsar rothschildi) on Nusa Penida Island, July-October 2006 (unpublished)

-

Dijkman, G. - Bali Myna takes flight to Nusa Penida (BirdingAsia Number 7 - June 2007); http://orientalbirdclub.org/birdingasia-7