Tana Toraja, the Land of plenty (2000)

Breathtaking views

Tana Toraja is the cool heart of South Sulawesi, the beautiful orchid-shaped island on the equator, at the centre of the vast Indonesian archipelago. Between 1996 and 1999 the author spent almost three years in this mountainous region, the coffee-producing highlands of 'Celebes'.

Its beauty is awe-inspiring, its culture unique and its people are warm, boisterously funny and friendly.

Its beauty is awe-inspiring, its culture unique and its people are warm, boisterously funny and friendly.

This page on Toraja is dedicated to the Torajans, to their unspoilt natural environment and to the friends who made the author's stay (1996-1999) a memorable one. May these pages be an inspiration for all those who plan a visit to Indonesia. Experience the spirit of these welcoming people, their attitude towards their indigenous religion in an otherwise Christian-based society, resulting in a magnificent culture. Witness the funeral ceremonies during the months of July to September, and take a long walk across Toraja's mountainous landscape, along scenic paddy fields and ridges with breath-taking views. And bring a pair of binoculars, since Toraja offers excellent birding opportunities.

The maximum temperature on record is 26 degrees Centigrade and the minimum temperature is 14. However, temperatures were higher during the extremely long period of draught in 1997, and the following wet monsoon with rainfall for days on end. The monsoons are known to be as whimsical as the seasons in the west...

Cool Breeze

After leaving stifling hot Makassar, Toraja offers a pleasant and refreshing climate. You can sit outside your hotel in the evenings or mornings and enjoy the crisp air, especially higher up in the mountains in places like Batu'tumonga (pictures below).

Like the rest of Indonesia, Toraja has two main seasons: a wet and a dry monsoon. The first one lasts from December through to March, while the second starts in June and ends in September, The periods in between are considered transitional periods. Typical weather for the dry monsoon is sunshine throughout the day with occasional short rainy spells. The wet monsoon, in general, offers sunshine in the morning with long spells of rain every day that start after 2 PM. When it is raining, it usually gets chilly and it is best to have a jumper or jacket ready.

Pala' Tokke, The Myth of the Gecko Man

Coming from Ke'te' Kesu', you drive 2 kilometres further up the road and take a dirt road signed "Pala' Tokke". You either walk from the main road or ride a motorbike until you get to a house on the right and paddies on the left. In the background you already see the rugged and gray cliff formations, and as you walk along the path between the bamboo forest, you reach a stone staircase to the grave sight.

Coming from Ke'te' Kesu', you drive 2 kilometres further up the road and take a dirt road signed "Pala' Tokke". You either walk from the main road or ride a motorbike until you get to a house on the right and paddies on the left. In the background you already see the rugged and gray cliff formations, and as you walk along the path between the bamboo forest, you reach a stone staircase to the grave sight.

Pala' Tokke is still a mystery and there are various stories about the place. Toraja people claim it means 'the arm of a gecko' in their language. It is the grave of a legendary figure in Toraja's history, who was noted for his ability to climb the cliff. He had the strength of a gecko, and could cling easily to the rock walls. When he died, his corpse was put in a hanging grave that was later hung in a style reminiscent of a gecko crawling on a wall. In fact, according to other sources, his whole family is buried here.

The spiritual world according to the Duri

The second interpretation, apparently, stems from the Duri people and differs from the Toraja version. In their eyes, Pala' Tokke is not the name of one person, but of a group of people who were able to climb the walls like geckos do. They seem to have been working class people with the name ma'pala'tokke, and their main task was to deliver noblemen's coffins to the mountain without using ladders. This was possible because their palms could easily cling to the cliff.

Hanging Graves

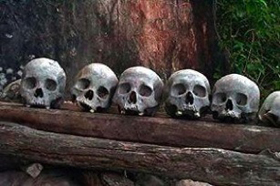

Image: one of the few remaining original house graves, at the left side of the protruding cliff.

You will find both hanging graves (erong) and a house grave (patane) after you have climbed the stairs. The house grave is especially beautiful since it is one of the few remaining house graves made of natural materials including alang-alang grass, wood, rattan and bamboo. The view is beautiful and on the right you will notice large holes in the cliff that have been left empty for many years. Whilst enjoying the view, be careful not to slip over the many scattered bones and fractured skulls on the ground beneath the grave.

The shrunken Mummy of Dende

As you go from Rantepao to Makale, and from there on to the Pongtiku Airport at Rantetayo, you turn right and gradually climb up a road that takes you through a myriad of the most spectacular panoramic views. Ask the villagers for the village of Dende, and they will direct you. You need good transport for this track, since the road turns into a gravel and stone dirt road after you have progressed a few kilometres from Rantetayo. Especially during the wet monsoon, make sure you take a four-wheel drive jeep or a trail motorcycle and a guide.

Image: mummy of Dende (detail), one of the marvels of Toraja (picture by Godi Dijkman, 1997)

Image: mummy of Dende (detail), one of the marvels of Toraja (picture by Godi Dijkman, 1997)

The road that leads up to Dende, takes you through the glowing hills near Makale and Madandan, which turn into rugged mountain ranges, with steep terraced rice fields and breathtaking views. The vegetation gradually changes from luscious green in the valleys to softer and more modest green in the mountains where mostly pine trees (buangin) and mountainous ferns grow. Nature, as anywhere in Toraja, is abundant and you will have a good chance of spotting some of the many species of raptures common to Toraja, such as the Brahminy Kite or the Crested Serpent Eagle.

In the village of Dende, you ask to see the Village Head (Kepala Desa) and he will show you the mummy, which is kept in his house. The mummy is said to be over a hundred years old, and the villagers claim it is a child. The head, though, is surprisingly small for the body, and it looks more like a tiny adult rather than a child. It is a neatly dressed human being of about 90cm whose skin in still intact, with perfect and slightly protruding teeth and somewhat thinned hair. Its bent fingers pop out from under the sleeves and the villagers keep putting coins in its hands as a sign of reverence or hope for good fortune and blessing. The people, who gathered around us as we were taking photographs, said that the mummy used to be 10cm taller and that it used to fit perfectly into its little red 'cradle'.

Everyone wonders about the mummy. Why has it shrunk, and why has it never shown signs of decay? As far as the villagers can recall, it has never given off any smell either. An explanation might be that in the olden days, before the introduction of Christianity, the body of the "sick person" (see Funeral Ceremonies) was "treated" according to Aluk To Dolo (see Religion) rules so as to prevent the body from decaying. This practice was continued even after the arrival of the Dutch missionaries, but then it was done by injecting formaline. Nobody we spoke to, however, could confirm either version, and the story of the shrunken mummy remains a mystery.

Tongkonan: Torajan Kindred Houses

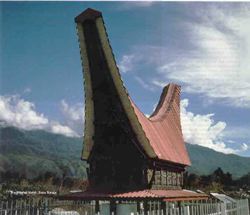

The most striking feature, perhaps, of Toraja is its houses. As you fly over Toraja, coming in via the South, you will see the small villages scattered in between the mountains covered with bamboo and veiled in mist. Most houses have the typical boat-shaped roofs, which, nowadays, are predominantly made of iron. The roofs used to be made of bamboo and other natural materials. The making of such a house was very laborious. The houses that you will see in villages such as Ke'te' Kesu' (near Rantepao) are the so-called tongkonan (from the Toraja word tongkon, which means 'to sit down'). These kindred houses are used for family purposes, and the construction involves the entire family clan.

History

Image: traditional village of Nanggala', in the North of Toraja

Image: traditional village of Nanggala', in the North of Toraja

According to myth, the first Toraja house was constructed in heaven by Puang Matua, the Creator (see: Religion). It was built on four poles, and the roof was made of Indian cloth. Next, Puang Matua ordered the construction of another house, on iron poles and a bamboo roof. When the ancestor of mankind descended to earth in the southern half of Toraja (in the area bordering the Regency of Enrekang), he imitated the heavenly house, and a big house ceremony was held for the occasion.

The former village founder of Toraja, an important figure in Toraja, was called Tangdilino'. Near Mengkendek (southern Toraja), a house was built that had a roof with its two ends bending upwards. This particular form is explained in various ways. The first story stresses resemblance to a boat - since, according to myth, the ancestors of the Toraja people came by boat from the Mekong Delta in South China - the second story claims that the arch-shaped roof looks like the sky. This is, indeed, reflected in some prayers by the ancient animistic belief Aluk Todolo.

Status and prestige

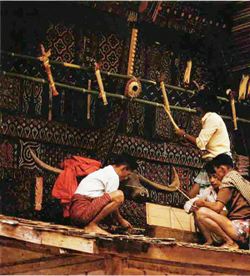

Image: men building and decorating a tongkonan

Image: men building and decorating a tongkonan

Historically, only the nobility has the right to build these elaborate and beautifully carved tongkonan. The most important noble houses were the seats of political power for local rulers who dominated small groups of villages. Each of these families has a long past, full of myths, mystery, and ancestral achievement. All noble families, of course, have a significant history to justify their claim to wealth and status, whereas most ordinary people live in undecorated houses - mostly bamboo shacks - called banua. Sometimes the status associated with a tongkonan and the people who are allowed to inhabit these houses, varies according to the different areas within Toraja itself.

Three different types of tongkonans can be distinguished. The first is called tongkonan layuk, which belongs to the highest adat authorities. This type of tongkonan used to be the centre of government - a position that even today seems to be respected. The second kind is the tongkonan pekamberan, which belongs to the family clan and group members surrounding the adat functionaries. The third kind is called the tongkonan batu, and belongs to the ordinary people (i.e. not adat functionaries).

The style of the tongkonans has changed slightly over time. The oldest surviving structures are generally small, with only a small curve to the roof. As the house came to embody aristocratic ambitions, it was gradually built higher and the curve of the extended eaves has become more and more exaggerated. As a consequence, the living space inside the tongkonan was reduced due to increased prestige and status, as the exterior of the house grew to be more colourful and exuberant in appearance.

House Decorations

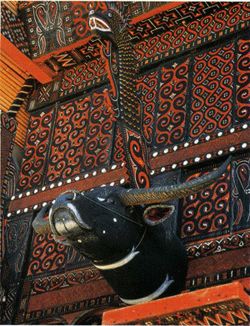

Image: buffalo head and the mystical Katik

Image: buffalo head and the mystical Katik

Many house carving designs are derived from plant and animal motifs. The names of these designs are reminiscent of everyday life, and very humble, for instance, pumpkin vines. Water plants and animals such as crabs, tadpoles, water weeds, and so forth are a sign of fertility. The trailing water plants, lusciously growing in all directions, are often depicted because they are able to multiply rapidly, while still clinging to the central stem. It is hoped that the house descendents will also be numerous and stick to the family clan.

Other carvings represent buffaloes, heirloom embellishments or heavy ears of rice. All of these motifs are connected to the desired wealth and abundance. The main wall poles, on the front of the tongkonan, are always decorated with stylised buffalo heads. On the top of the façade, in the gable triangle, there are images of beetle nut and sunbursts, since some take this part of the tongkonan to represent the Heavens. Of course, being the mediator between earth and heaven, cocks are always a part of the decorations. The most mysterious of all creatures that is sometimes found on the front of a tongkonan is the so-called katik, a big, long-necked bird with a crest on top of its head. This is either a cock, or a mythical bird of the forests. Some, however, claim this is a hornbill, the image of which is often used all over South-East Asia.

Relation with the spiritual world

Image: modern tongkonan (at a grave sight) with an iron roof

Image: modern tongkonan (at a grave sight) with an iron roof

The layout of the Toraja adat houses is imbued with symbolic meaning. The orientation of the tongkonans has cosmological connotations, and the design of the carved decorations on the front has symbolic significance since it contains a variety of messages about social hierarchy and structure, and the relations to the world of the spirits.

As described above, the creator Puang Matua is associated with the North, and therefore the tongkonan must also face North. The South of the house is associated with the afterworld (heaven, or Puya) and the ancestors. The West and the East are associated with the left and right hands of the human body, but also with the world of the gods (East) and the ancestors in their deified form (West).

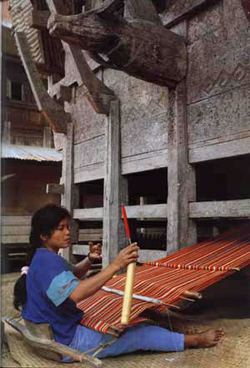

Ikat Weaving

The technique of 'ikat' - literally: to link, to bind - is something that is done worldwide, but nowhere is the technique so refined as in Indonesia. The weaving of ikat is a very laborious and time-consuming process. You only have to watch the women weavers at work to realise that it takes months for one ikat to be completed. The weaving technique probably stems from ancient China.

The technique of 'ikat' - literally: to link, to bind - is something that is done worldwide, but nowhere is the technique so refined as in Indonesia. The weaving of ikat is a very laborious and time-consuming process. You only have to watch the women weavers at work to realise that it takes months for one ikat to be completed. The weaving technique probably stems from ancient China.

Function and use

Large warp ikats are produced in Kalumpang with striking geometrical patterns. The ikats, which come in various qualities and thickness, were used in funerary rites. The pori lonjong (long cloth) was hung on the walls of the death house, or used to make textile pathways along which, according to the ancient religion Aluk Todolo, the dead could reach heaven (Puya). The seko mandi, large square cloths, were mainly used as shrouds, but could be hung as a canopy over the corpse or combined with others to create a sheltered area for the funeral guests. In the period in which the deceased is considered "sick" (see: Funeral Ceremonies), the body is wrapped in a lot of ikats and other cloths. This period can last for several days or weeks up to a year, and the widow must sit in the death house by the corpse until the actual funeral is performed.

Ikat weaving centres

In Sulawesi there are two centres of ikat weaving: Rongkong and Kalumpang, both situated in the more isolated areas of Torajaland. The closest to Tana Toraja is Kalumpang, in West Toraja, north of Mamasa. Mostly, the ikats that are made in Kalumpang are sold and distributed to Central Sulawesi (to the North) and Malimbong (close to Sa'dan) to the South. However, ikats are also made in Toraja and you can see people weaving them in villages such as Sa'dan and Lemo. Most ikats that are offered for sale are new but just as beautiful as old ones.

Colouring

In the past, the large ikat cloths were used in Tana Toraja as fines and to act as pledges of peace between feuding members of the upper casts. They were made exclusively from hand-spun cotton that was grown in home gardens and the dyeing-process could take many months. The traditional colours used in Toraja ikats are reddish brown, cream white and grayish dark blue. All of these colours were traditionally made from natural dye materials. The red colouring in ikats was derived from a mixture of morinda, dammar resin and chilies, and blue came from Indigo and torae grass mixed with ink fruit. The typical colouring of Toraja ikats is blue, black and white against an apricot background, and traditionally blue weft (horizontal) threads are used.

In the past, the large ikat cloths were used in Tana Toraja as fines and to act as pledges of peace between feuding members of the upper casts. They were made exclusively from hand-spun cotton that was grown in home gardens and the dyeing-process could take many months. The traditional colours used in Toraja ikats are reddish brown, cream white and grayish dark blue. All of these colours were traditionally made from natural dye materials. The red colouring in ikats was derived from a mixture of morinda, dammar resin and chilies, and blue came from Indigo and torae grass mixed with ink fruit. The typical colouring of Toraja ikats is blue, black and white against an apricot background, and traditionally blue weft (horizontal) threads are used.

The colouring materials applied to the traditional tongkonans (family houses) are different: red, yellow, white and black. Black soot is taken from cooking pots to provide the black colour (associated with death), while red and yellow earth are used to provide these two colours, respectively human life and purity. White is made from lime. The last three colours are mixed with palm wine to enhance the staying power.

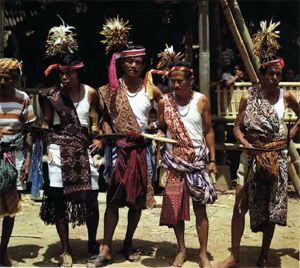

Image: true display of colourful feathers, batik and ikats at a funeral ceremony in Toraja

Motifs

The motifs in ikats generally represent ancestors or water buffaloes, but tend to be so abstract that the figurative can hardly be recognised. In general, the designs are dramatic arrows and triangles, alternating with zigzag motifs and the sekon (hook and rhomb), that represents a human figure, and is present in the majority of ikats. Toraja weavers tie a double thickness of warp threads to enhance the dramatic effects of the images.

Modern Ikats

Modern Ikats

Due to the anti-government rebellions in the 1950s, the weaving centres of Rongkong and Kalumpang showed considerably less activity in the following period. Today, these centres produce imitations of the traditional cloths for tourists, and are sold at various places in Tana Toraja. These new ikats are usually made from machine-spun cotton and can make stunning wall or floor decorations.

Megalithic Stones of Toraja

The funeral rituals of the highest cast in Tana Toraja, the so-called Tana' Bulaan take place in a ritual field Rante where stones are erected as a symbol of the nobility for the Rambu solo' Rapasan ritual, the highest traditional funerary ceremony. The erection of the stones in the Rante is part of the ancient Torajan belief Alukta or Aluk To Dolo (the belief of the ancestors). The Rapasan ceremony lasts for seven days and seven nights, and 12-24 waterbuffaloes are slaughtered in the central Rante.

The megalithic stones are long and ovally shaped, like menhirs, rather flat with a pointed and blunt end at one side. These megalithic stones are hard to find, and if found, their shape is often hidden because they are partly covered with earth.

Orang mangimbo atau doa2 yang dipimpin oleh Tominaa atau pendeta Alukta, sebelum mulai pengalian. Diharapkan natinya dapat batu yang besar dan bagus bentuknya yang dipercaya dapat pula memberi keberuntungan. Dikorbankan seekor babi setiap hari selama penggalian, kadang2 dibutuhkan waktu tiga sampai lima hari.

Sejak hari pertama menarik simbuang, maka dimulailah mangorbankan kerbau. Seekor kerbau dikorbankan setiap hari, kadang2 dibutuhkan waktu tiga hari sampai berminggu-mingggu untuk menarik batu simbuang ke Rante. Puluhan sdampai ratusan orang datang membantu, juga dari desa2 tetangga sebagai tanda solidarits & kegotong-royongan. Kerbau dipotong di tempat yang diperkirakan akan mereka capai saat istirahat & makan siang.

Ada seorang yang memberi aba2 sambil berdiri di atas batu yang ditarik. Kadang2 tali-temali tersebut dari bambu putus, sambil tali-temali yang baru dipasang banyak yang ma'badong yaitu tarian & nyanyian kedukaan mengelilingi batu tersebut dengan saling mengandengkan jari keliling. Mereka dapat berhenti & beristirahat beberapa hari untuk memulihkan tenaga atau oleh karena gangguan cuaca seperti hujan.

Sesampainya di Rante, ujung batu yang lebih besar ditanamkan di lubang yang telah digali kira2 se[ertiga dari panjang atau tingginya batu simbuang. Sedangkan dua pertiganya menjulang tegak dengan kokoh menghadapkan sisinya yang dianggap depannya ke arah yang baik. Semakin banyak kali upacara pemakaman Rapasan diadakan di Rante, semakin bertambah jumlah batu 2 simbuang yang didirikan. Batu simbuang digunakan juga sebagai tempat untuk menambatkan kerbau selama upacara Rambu Solo' berlangsung sampai pada hari pemotongan kerbau.

Masih ada juga bangsawan Tana' Bulaan pada waktu upacara Rambu Solo' Rapasan yang mendirikan batu simbuang di Rante sampai sekarang. Tetapi kebanyakan batu yang mereka gunakan adalah batu simbuang pahatan.

Di TTR hampir setip kampung memiliki Rante: Umumnya dalam satu areal Rante kita dapat antara 15-35 buah batu simbuang yang ukuran tinggi besarnya ---. Ada yang bentuknya lonjong pipih & ada juga yang besar bulat lonjong yang ujungnya mengecil agak lancip & tumpul. Ada yang berdiameter antara 15cm - 1m, dengan tinggi mulai dari permikaan tanah antara 1m-5m.

Simbuang2 yang berasal dari jenis batu karang, atau batu kapur (limestone) yang kebanyakan berbentuk pipis lonjong banyak kita dapati di daerah TTR bagian timur & selatan. Sedangkan simbuang2 yang berasal dari jenis batu basalt atau granit kebanyakan berbentuk lonjong banyak kita dapati di daerah bagian utara & barat Tana Toraja.

Tidak ada yang tahu secara pasti kenapa orang Toraja memulai mendirikan batu2 simbuang, tetapi ada yang memperkirakan sejak 300-350 tahun yang lalu seumur dengan kuburan batu pahat atau liang pa'. Ada juga yang memperkirakan sudah lebih dari ribuan tahun yang lalu.

Forlorn Glory of Sirope

Forlorn Glory of Sirope

A little blue sign caught our curiosity. Half way between Rantepao and Makale, on a side path leading from a sharp steep bend in the main road, a half-withered sign promised a glimpse of forlorn glory.

After about 20 minutes of easy walking, the path splits into two narrower paths. The left one leads to Lemo, one of the major Obyek Wisata (tourist attractions), and the right one is signed to 'Sirope Stone Grave'. The location is well hidden from wanderers, a blue sign in the village close-by shows you where to go. Once you descend from the village, you pass through two huge rugged rocks in the midst of dense foliage, and discover a huge white-gray cliff with typical square burial holes in it.

There is something odd about this grave sight. On the left, there is a new patane (house grave) with a recently buried person in it. In the centre and bottom right, you find half-decayed old coffins, with bones and broken skulls sticking out of them. On top of one of the oldest coffins is a tiny photograph of a girl, tenderly smiling, who apparently died at a young age. It is obvious that people are still working on this grave, piles of sand and stones are scattered around everywhere, but at the same time it looks deserted.

Looking up, I found the explanation for these thoughts. In between the holes closed with wooden doors, there are oblong carved places meant for the tau-tau, the effigies of the dead. These places are empty, and should have been filled with the small puppets meant to represent the deceased. Normally, these tau-tau are the second puppet version made after the dead person has been buried, In Sirope, however, these tau-tau have disappeared.

Looking up, I found the explanation for these thoughts. In between the holes closed with wooden doors, there are oblong carved places meant for the tau-tau, the effigies of the dead. These places are empty, and should have been filled with the small puppets meant to represent the deceased. Normally, these tau-tau are the second puppet version made after the dead person has been buried, In Sirope, however, these tau-tau have disappeared.

According to the locals, they were stolen about 8 years ago and were never replaced. We spoke to the guard, who then was in control of the place, and he still remembers that day with sadness. Sirope is located in a sparsely populated area, where thieves have a good chance of stealing unnoticed. In other places of interest, like in Lemo, exact copies have replaced the stolen effigies. Sirope, however, is still waiting...

Papa Batu Tongkonan

It took us a long time to figure out how to get to Papa Batu. The tongkonan we were looking for was located at the end of a walking trail, some 30 minutes from the main road in the centre of the village of Rembon (Saluputti area). The trail is easily accessible, passing a long bamboo hanging bridge, it takes you past lovely paddy fields, great views, and scattered houses and - as everywhere in Toraja - warm and friendly people. After about 20 minutes, you arrive at the bottom of a stairway that leads you up to a truly unique sight in Toraja: the Tongkonan with a stone roof. At first sight, this tongkonan does not seem to be that special. Only after having scrutinised it carefully do you realise that this is something quite unique.

Image: stone tiles are held together by rattan

Image: stone tiles are held together by rattan

Roofing

The rooves of most traditional tongkonans are made of either bamboo or wood (wooden tiles), including the tongkonans in the centre of Makale. Nowadays, the roofs of most tongkonans are made of iron or zinc sheeting, something that is considered as an eye-sore by most tourists. To the Toraja people, however, it is an economic alternative to the laborious and more expensive roofs made of natural materials. The roof of this tongkonan papa batu (Toraja language for 'stone roof') is made of stone that was quarried out of big round rocks that are found all over Toraja. The most beautiful and well-known example of a stone grave in Toraja is Lo'ko' Mata', located just a few kilometres west of Batutumonga'. This type of stone was used to cover the roof of this tongkonan. A hole is made in the carefully sculpted 'tiles', and they are attached to wooden planks by strings of rattan, as you may observe in the photograph on this page. Rattan is said to be stronger than iron rod, since it does not rust or decay, providing that it is not exposed to the rain. Some stone tiles have fallen to the ground and have never been replaced properly. Therefore, the upper part of the roof is now covered with ordinary red roof-tiles.

Four Rooms

Papa Batu is believed to be over 250 years old, which makes it one of the oldest surviving tongkonans in Toraja. Apart from its age and the unique roofing, the feature that makes this a special attraction, is that it is the only known tongkonan with 4 rooms. Usually, the space inside a tongkonan is divided into three rooms. Papa Batu, however, was special and belonged to a royal family called 'rajas'. The king used to live in the 'state' room facing south, the pandung. Next to the royal room you find a room that was occupied by the king's family, the so-called ninan.

As you enter the tongkonan, you see the central and biggest room, which was used for receiving guests or as a place to put the coffin of a dead person before the funeral. This central room is called sali. On the North side, you find the room that was inhabited by what people now euphemistically refer to as the guard, but what used to be the slave(s), the Kaunan-people. This room is the smallest and is called bondon.

Image: the tongkonan seen from the north

Image: the tongkonan seen from the north

Magic Skull

In the sali, quite a dark room in the absence of windows, you will find a curious skull of a young buffalo attached to a central pole against the wall. You will also see some rice ears hanging from it, dangling off its horns. The guard from next door, a very sympathetic and helpful old man who still works for the government, informed us that this skull has magic power. Until quite recently, this skull was used to cure headaches. People suffering from headaches came to Papa Batu and offered a few rice ears to the skull. A handful of water was put on top of the skull, and was gathered in the hands below. The water that had passed the skull, had assumed magical powers whereby headache would disappear in an instant.

Kambean

In addition, what makes this an interesting and unique traditional Toraja house, is the fact that this tongkonan has a central "royal" pole, called the Kambean in Toraja language, which is perhaps its most unique feature. Normal tongkonans do not have this support in the centre. This sturdy and grayish pole that supports the entire tongkonan can best be observed from the south side and is said to possess magic powers as well.

There are stories of visitors who felt ill after touching the royal pole and entering the tongkonan without having asked for permission. So, if you decide to venture out to Rembon, and visit the stone roofed tongkonan, you had better call on the neighbour first.

There are stories of visitors who felt ill after touching the royal pole and entering the tongkonan without having asked for permission. So, if you decide to venture out to Rembon, and visit the stone roofed tongkonan, you had better call on the neighbour first.

Conservation

As was clear from the state of the roof, this tongkonan desperately needs repair. The stone tiles are not replaced properly - as the tiles break when they fall on the ground - but also the carvings on this tongkonan are withered, look pale and have lost colour. There used to be another of this type of tongkonan just beside it, at the south side, but that one has fallen to pieces. If nothing is done about this, the only remaining stone roof tongkonan will disappear forever.

Fortunately, however, there seem to be initiatives to conserve this tongkonan. Some NGOs within and outside of Toraja have managed to allocate funds for the restoration of Papa Batu. It would be truly shameful if Toraja's heritage is left to the whims of the gods and weather.

Source

- texts & photographs by the Godi Dijkman were originally published at toraja.net (now dysfunctional)