Calon Arang (2009)

Below Dutch article is a rendering of Calon Arang, written May 2008, published autumn 2009. The ancient, manysplendoured story of Calon Arang is a classical Balinese representation of the battle of good and evil, between Rangda and Barong, witnessed in the form of a sacred street performance in Bali, autumn 2007. The author thought he was immune to a bit of Balinese magic. Little did he know... (English translation by the author, Dutch orginial below).

Below Dutch article is a rendering of Calon Arang, written May 2008, published autumn 2009. The ancient, manysplendoured story of Calon Arang is a classical Balinese representation of the battle of good and evil, between Rangda and Barong, witnessed in the form of a sacred street performance in Bali, autumn 2007. The author thought he was immune to a bit of Balinese magic. Little did he know... (English translation by the author, Dutch orginial below).

Calon Arang: Spectacular Balinese Road Theatre (May, 2008)

The gamelan orchestra begins to play, and out of nowhere the first actors appear. The story performed tonight is perhaps the most ancient and sacred stories of all Balinese religious tales, brought down from ancient Java on lontar palm leaves, the Calong Arang. It is about the battle between good and evil. The start of the spectacle is relaxed, in bright lighting and accompanied by gay gamelan music, comical scenes with arguably funny slapstick effects as an introduction to the more grave scenes of treachery and deceit. Amidst the smaller Balinese I stand out quite visibly for I'm two metres tall and hardly aptly dressed. But soon I discern two other tourists amongst the multicoloured crowd, dressed in drab, odd-sized sarongs. This performance is a sacred one, not meant for tourists and, hence, cameras are not allowed. Apart from a handful of lucky if underdressed tourists, all Balinese present at this spectacle are clad in traditional attire fit for the occasion. The atmosphere is subdued and one of excitement at the same time and people are a little wary, gazing at noting in particular. A little while afterwards, I was to find out why.

The suggestion of going to watch this spectacle came from Francis, a friend who has spent half a lifetime on the Island of the Gods and has made Bali his home. He is an expert on Balinese culture and he confided to me that this was truly a rare occasion. Earlier that day he recounted stories of scary dragons and ominous masks with big, bulging eyes. I did not think much of it and thinking of myself as a rational individual, I thought I was able to handle a bit of magic, ghost stories and monsters. Reality that evening, however, proved otherwise.

It all starts at around half past nine in the evening. In front of me trots our guide from the Puri Gede (Great Palace) in the village. In the frond courtyard of the palace there is a tree in which - according to legend - lives a ghost. We pass the tree in reverent silence. The atmosphere 'on stage' is relaxed, some people here and there chatting and eating snacks, staring at their coffee.

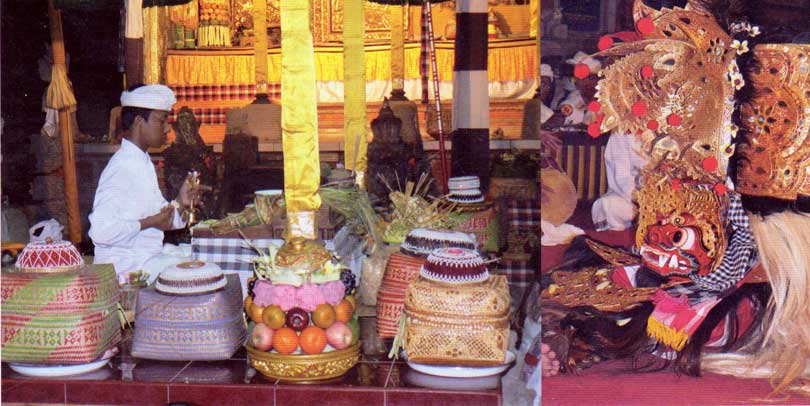

A part of the road in the middle of the village, adjacent to the Pura Dalem of the village, has been designated for the evening's events. First, we take a look at the ongoing proceedings in the temple, and discern the various holy masks, praying people, the high priest and various low priests who occupy themselves with offerings, baskets towering with fruit, women running to and fro with banana leaves, flowers of any imaginable size and colour, platters filled with incense, a young piglet in a white bag, some chicks and a single duck. I am discovering the invisible way the Balinese organise themselves. On the face of it, it all seems but a scuttling about, moving objects from one place to another, without any system, rhyme or purpose. But nothing is what it seems: the arbitrariness of organised chaos, as if directed and orchestrated by invisible threads from above.

Preparations gain a different character when I am gracefully given a hint of stepping outside the temple: behind me an entire chorus of men sit cross-legged on the floor with arms and hands in unison, in what looks like a balé. They clutch their hands together and while holding them in front of their foreheads, they remain deep in prayer in the direction of Rangda's mask which is placed on the highest and most holy position in the temple. I look at the mask, and am overawed by its piercing and uncanny look, with bulging eyes, fearsome fangs and a wild-looking, ochre-yellowish bundle of hair. With much trepidation, I seek the shortest way out of the temple.

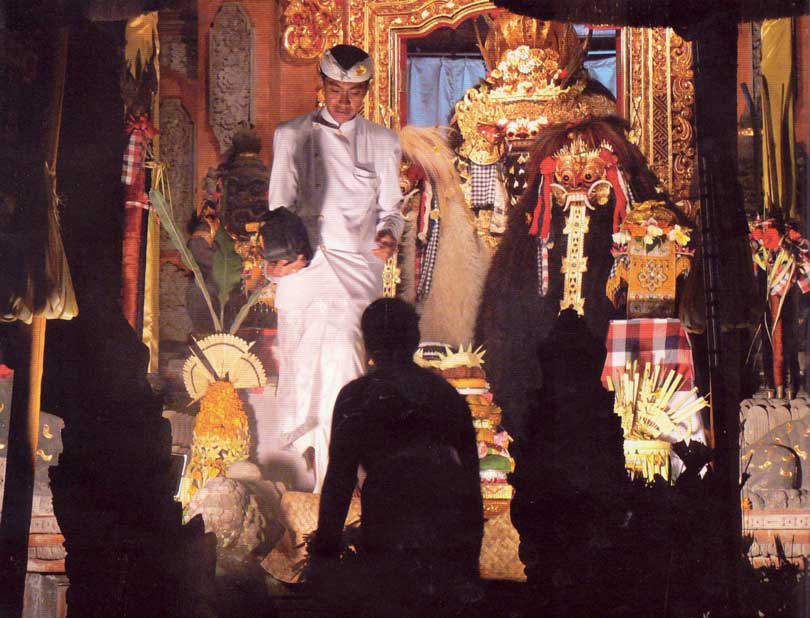

For this occasion, I am optimistically clad in traditional Balinese clothes: a white kain with a simple yellow sawtooth-motif at the bottom, covered by a claret saput, a white embroidered shirt, and a headband called 'udeng' - which is tied together by straps on the front. I had it done for me, since it proves more difficult than I imagined. A red hibiscus flower completes the 'transformation', pinned in the white headband with the flower pointing upwards. I get a good chance of looking around carelessly, observing the scene with growing apprehension.

After some wandering about, we choose the most convenient place, since we will have a chance of observing the spectacle at its best. At our left stands a rather small stage on scaffoldings from where Rangda will eventually appear and descend towards the main stage. On our right, the temple is getting increasingly busier: people are making their way across the stage from the temple to one of the balés, carrying baskets or arranging the lighting and microphones. People start to gather along the sides of the tarmac, closely together, while more and more people sit down on all sides. What normally is an ordinary village road, is turned into a proper stage.

I now have to stand up since, in front of me, a crowd of giggling boys have taken hold of the only left space on the tarmac. They all look very manly, slapping each other on the back, squatting close together, laughing at the performance but - as it appears - this is to hide their terror of what is to come. The atmosphere changes, lights are dimmed and the gamelan music alters into an altogether threatening note. The witch Calon Arang, in one of her embodiments, enters the graveyard in semidarkness where shortly before a still-born child was buried. With six of her attendants, all skilled in black magic, she digs the child out of the grave and takes it with her. This enrages the king, since his reign has been the scene of numerous illnesses and plagues and suspicion falls on Calon Arang, who, with her evil practices sows despair and death on the land. The king and his entourage, in Old-Javanese, challenges the witch, only after a Balian (witch-doctor) appears on the stage in a comical act, involved in long-winding and spun-out conversations which never cease to endear the audience. He enacts bewilderment, sexual extravagance, and converses with his attendants in a lively fashion. In comes the invisible witch, and dances around ominously, wildly. She casts a spell on him, and he enters into a trance. The Balian is carried off in a spasm.

I now have to stand up since, in front of me, a crowd of giggling boys have taken hold of the only left space on the tarmac. They all look very manly, slapping each other on the back, squatting close together, laughing at the performance but - as it appears - this is to hide their terror of what is to come. The atmosphere changes, lights are dimmed and the gamelan music alters into an altogether threatening note. The witch Calon Arang, in one of her embodiments, enters the graveyard in semidarkness where shortly before a still-born child was buried. With six of her attendants, all skilled in black magic, she digs the child out of the grave and takes it with her. This enrages the king, since his reign has been the scene of numerous illnesses and plagues and suspicion falls on Calon Arang, who, with her evil practices sows despair and death on the land. The king and his entourage, in Old-Javanese, challenges the witch, only after a Balian (witch-doctor) appears on the stage in a comical act, involved in long-winding and spun-out conversations which never cease to endear the audience. He enacts bewilderment, sexual extravagance, and converses with his attendants in a lively fashion. In comes the invisible witch, and dances around ominously, wildly. She casts a spell on him, and he enters into a trance. The Balian is carried off in a spasm.

As the music carries on, and the atmosphere turns grim, with the gamelan music that evokes dark, slow tunes that deepen into the consciousness, arousing a dark and ill feeling of tension, I am so transfixed on what is going on stage that I almost miss the events unfolding to my right. In the middle of the audience, at the right side of the temple, two girls are screaming hysterically. They are being plucked out of the crowd and carried off to the Pura Dalem temple. From a distance I discern, between a few onlookers in front of me, how these girls in the temple are overpowered by a number of priests, spasmodically stretched bodies, wailing and screaming. And, indeed, another one, this time a youth who, right in front of me, stretches up into a spasm and jumps wildly into the people around him. And yet another one, this time a young boy of say not older than ten, he faints with stretched limbs, his face tense with emotion. The actors too, drop onto the stage-tarmac. Their masks are removed and yelping they are carried off to the side. People are screaming, and a sudden spasm of emotion lashes out over the audience. Various stern-looking men position themselves amidst the crowd and on the tarmac to make sure nothing runs out of hand.

Calon Arang, who has seen a number of incarnations, is challenged by the king's ambassador. He speaks in a harsh and ominous tone of voice, uttering words that come from the back of his throat. He waves about his arms holding his keris upright: "Come forward, you coward, you are nothing, come here and show us you earn our respect. Who are you to spread all this evil? Take up this challenge and come hither!" he utters in Old-Javanese.

All of a sudden, it looks like people are dropping like flies, the atmosphere is one of excitement and tangible tension, the gamelan orchestra plays with an undertone of sacrality and challenge, one feels the quivering notes in the lower region, changing between fast and slower rhythms, daunting and threatening. I am oblivious of the fact that - after hours - I can hardly bear to stand on my legs anymore. One of the actors is having a fit and with great violence crashes into the crowd just in front of me. He falls to the ground in a spasm. Behind me, an elderly lady is screaming hysterically, with her arms stretched out into the air, supported by three men. An undercurrent of panicky agitation spreads around, and people are screaming everywhere.

The epitome of the performance is nigh. Seated in a row on the tarmac, about five priests take their stance and sit down amidst a row of offerings, pisang leaves, bamboo trays, bottles of arak and again many fuming bundles of incense. In a matter of seconds, the tiny piglet's throat is slit by four priests and still gaping for air, its head is put on a ritual bamboo salver, its legs behind its ears. Much holy water is sprinkled around in all directions and the smoke of incense is thick all around. Then, finally, from high scaffolding, Rangda - in her proper and sacred appearance - descends onto the stage, with her spell-bounding mask. The mood in the audience swiftly switches into one of utter angst. I get a queasy feeling in my stomach, as if I am going to get sick and quickly look at my companion for comfort. He, too, is past smiling. Tension lies as a thick blanket over the crowd. Through a dense mist of incense smoke I observe a massive-scale psychosis roaring through the packed crowd. Some thirty men lie on the tarmac twitching their limbs, spasmodically moving their bodies, foaming mouths. The old lady at the back of me now is screeching, and one girl after the other is taken to the temple. They fail to wake up from their trance, and their bodies convulse beyond control, despite many sprinklings with holy water.

At this stage, the scene is full of people. Rangda is facing her opposite, the magical Barong, a mythical lion-like creature similar to the Chinese dragon. The Barong is enacted by two men and represents the good as opposed to Rangda, the embodiment of evil. Together, the entranced men perform a massive attack on the witch. She dances in a staccato fashion, arms hanging down, jerking her limbs up and down, adding to the macabre image of death she represents. Krises are being flung about and suddenly all the entranced men, as if in one body, furiously point their kris at the witch who during ten minutes or so is being attacked from all sides by men who try to stab her to death, to defy evil and overcome lower sentiments by trying to outdo their worst enemy, Rangda. In the meantime her mask is removed, since it would get crushed in the onslaught. The massive attack continues, and even the witch-doctor offers himself to be stabbed by the spirited crowd of men armed with krisses. The old woman behind me faints and falls into a spasm on the floor.

The drama ends as suddenly as it began. The man enacting Rangda gets his share of holy water plentifully sprinkled over his whole body. He removes his 'bullet-free' vest. The actors gradually retreat into the temple area. The men who went into a trance are pushed up until they can stand. Not everyone, however, is ready to accept the expected state of consciousness, and while still quivering with convulsion they are carried away. A firm twitch beneath the arms, up you go my lad, the evening is over! Lights are switched back on, and the crowd disperses rapidly into the surrounding darkness. The gamelan orchestra has stopped playing and the air of wild hysteria has evaporated in thin air.

The drama ends as suddenly as it began. The man enacting Rangda gets his share of holy water plentifully sprinkled over his whole body. He removes his 'bullet-free' vest. The actors gradually retreat into the temple area. The men who went into a trance are pushed up until they can stand. Not everyone, however, is ready to accept the expected state of consciousness, and while still quivering with convulsion they are carried away. A firm twitch beneath the arms, up you go my lad, the evening is over! Lights are switched back on, and the crowd disperses rapidly into the surrounding darkness. The gamelan orchestra has stopped playing and the air of wild hysteria has evaporated in thin air.

While I rub my queasy stomach, I slowly walk back to the palace, with Francis at my side, looking distinctly pale this time. Are we in need of someone to show us the way back home in the dark?, somebody asks in a friendly voice. Oh yes please, Francis replies the kind palace dweller. After all, you never know, being on one's one is perhaps not a good idea at this time of night, given the ghost in front courtyard of the palace. Silently, and a little disturbed, I cannot stop wondering if evil has outwitted good, or perhaps the other way around...

* Dutch Original article *

Calon Arang: Spectaculair Balinees straattoneel

Het gamelanorkest begint te spelen en uit het niets verschijnen de eerste acteurs. Het verhaal dat vanavond wordt opgevoerd is wellicht het oudste en meest sacrale uit Bali, de Calon Arang. Het gaat over de strijd tussen goed en kwaad. Het begin van het spektakel is relaxed, in fel licht en met vrolijke begeleiding van gamelan, komische scènes met een koddig slapstick-effect, een inleiding naar serieuzere scènes van bedrog en verraad. Tussen de kleine Balinezen val ik op door mijn lengte, maar al gauw zie ik twee lange toeristen gehuld in veel te lange sarong ronddwalen. Gelukkig mogen ze geen foto's nemen; deze heilige voorstelling is nou eens niet voor toeristen. Buiten de paar verdwaalde westerlingen zijn alle aanwezige Balinezen in tempeltenue. De sfeer is gelaten en gespannen tegelijk; men staart wat vaag voor zich uit. Ik zal later merken waarom.

Het idee om naar deze voorstelling te gaan kwam van Francis, een kennis die al jaar en dag in Bali zijn tweede huis heeft. Hij is een expert op het gebied van Balinese cultuur en had me warm gemaakt voor deze speciale avond. Eerder op de dag vertelde hij verhalen over draken, onheilspellende maskers met grote uitpuilende ogen. Ik vond het allang best. Als nuchtere, uit de klei getrokken Hollander kan ik best tegen een beetje magie, spookverhalen en monsters, dacht ik.

Het begint uiteindelijk tegen negen uur 's avonds. Voorop loopt onze begeleider van het Puri Gede, een van de paleizen van de omgeving. In de voorhof van het paleis staat een boom waarin, zo gaat de legende, een spook huist. We passeren de boom in gepaste stilte. De sfeer op het 'toneel' is ontspannen, wat mensen hier en daar staren voor zich uit. Ze hangen bij één van de warungs langs de weg, kletsend aan de kopi tubruk.

Een weggedeelte in het midden van het dorp is afgezet, grenzend aan de Pura Dalem, de tempel der doden. Eerst nemen we een kijkje in de tempel, en kunnen de verschillende heilige maskers, biddende mensen, de hoge priester en verschillende priesters bezig zien met offergaven, manden met fruit, vrouwen met bananenblad, veelkleurige bloemetjes, schalen met wierook, een biggetje in een jute zak, kippen en een enkele eend. Inmiddels ontdek ik dat er een onzichtbaar systeem van organisatie bestaat hier in Bali. Het lijkt of ze maar wat doen, maar niets is hier wat het lijkt: de willekeur van een georganiseerde chaos, als door onzichtbare draden van boven aangestuurd en gesynchroniseerd.

De voorbereidingen van het schouwspel krijgen al rap een ander karakter als ik de tempel word uitgewezen: achter mij zit een heel koor van mannen in kleermakerszit op de vloer, handen bijeengevouwen tegen het voorhoofd, biddend naar het masker van Rangda dat op de hoogste plek in de tempel staat. Een waar onheilspellend masker, met grote bollende ogen, opvallende slachttanden en en wilde bos gelig haar. Beduusd maak ik dat ik weg kom.

Voor deze unieke gelegenheid heb ik mij in traditioneel tenue gehuld: een witte sarong met geel tandmotief aan de onderkant, een bordeaux-rode saput er overheen geslagen, een hagelwit shirt met witte borduursels erop. Ik draag een Balinese hoofdband die je aan de voorkant vastknoopt, of vast laat knopen, want zo handig ben ik daar nog niet in. Een grote, rode hibiscusbloem maakt het geheel compleet, zodanig vastgespeld dat de deze naar boven wijst en duidelijk te zien is. Ik kan ongestoord rondneuzen, en ik geef mijn ogen goed de kost.

We kiezen de beste plek uit, want - zo legt Francis uit - dan kunnen we het hele spektakel goed volgen. Links van ons staat en verhoogde stellage van waaruit de Rangda neer zal dalen. Rechts is de ingang van de tempel die alsmaar drukker wordt, het is is inmiddels een komen en gaan van mensen. Iedereen is in de weer, gaat zitten langs de kant van de weg, beschenen door het licht van felle spotjes, en er komen allengs steeds meer mensen bij. Microfoons zijn op twee plaatsen over de weg gespannen om de het toneelspel boven de gamelanmuziek en het rumoer van de menigte uit te laten klinken.

Dan begint het gamelanorkest te spelen en uit het niets verschijnen de eerste acteurs. De Calong Arang, het verhaal dat vanavond wordt opgevoerd, heeft zijn wortels in Oost-Java en is met de verdrijving van het Hindoe-Boeddhistische Majapahit-koninkrijk in het begin van de zestiende eeuw naar Bali overgewaaid. De Calon Arang getuigt van het oeroude beginsel dat mede vorm geeft aan de beleving van het Hindoegeloof op Bali: wie laat zich kennen als de sterkste macht in het eeuwige gevecht tussen het goede en het kwade? Af en toe buigt Francis zich fluisterend naar me toe en legt uit dat de acteurs nu eens in het Balinees, dan weer in het Hoog-Javaans spreken. Taal is verbonden met status en macht, en daarmee bij uitstek een instrument om aanzien te laten blijken.

Nu moet ik toch echt gaan staan want voor me hebben een stel giechelende jongens plaats genomen, heel stoer allemaal, maar - zo blijkt - doodsbang. De sfeer verandert, de lichten dimmen en de gamelanmuziek wordt dreigend. De heks Calon Arang, aanwezig in verschillende gedaantes, betreed in halfduister het kerkhof waar een doodgeboren kind is begraven. Met haar zes leerlingen in de zwarte magie, de Sisia, graven ze het kind weer op en nemen het mee. Dit wekt de woede van de koning, het land wordt immers geteisterd door ziekte en plagen en de verdenking valt op Calon Arang, die met haar duistere krachten onheil over het land zaait. De koning en zijn gevolg, in oud-Javaans, daagt de heks uit, nadat de Balian, een Balinese sjamaan, ten tonele wordt gevoerd in een komische act. De Balian voert lange en hilarische gesprekken met zijn begeleiders en wordt betoverd door de voor hem onzichtbare heks. In trance wordt hij afgevoerd.

Terwijl het spel verder bezig is, en de sfeer grimmiger wordt, met de gamelanmuziek die nu een onheilspellende dreun speelt, ontgaat mij bijna dat aan de rechterkant van de tempel al twee meisjes hysterisch zijn gaan gillen. Ze worden uit de menigte gevist en naar de Pura Dalem gedragen. Van een afstand kan ik tussen een paar hoofden net zien dat ze in de tempel gillend en schreeuwend overmeesterd worden door een mangku, een lage priester. Verhip, nog één, deze keer een jonge vent die recht voor me in een stuiptrekking een paar meter het publiek in springt, en nog één, een jongen van nog geen tien jaar oud. Ook de toneelspelers vallen erbij neer op het trottoir. Hun masker wordt afgedaan en kermend worden ze afgevoerd. Mensen schreeuwen, een golf van emotie rolt uit over het publiek. Op straat, het toneel, staan inmiddels diverse mannen die het spel begeleiden en ingrijpen waar nodig.

Calon Arang, die al in een paar verschijningen te zien is geweest, wordt verder uitgedaagd door de afgezand van de koning. Hij praat in een harde, vijandige toon, met een bulderstem die komt van achter in zijn keel. Hij zwaait vervaarlijk met zijn armen en kris: "Kom op lafaard, je bent niets waard, kom hier en laat zien dat je iemand bent. Neem mijn uitdaging aan", gaat het in donderende taal.

Ineens is het alsof er mensen bij bosjes neervallen, de sfeer is opgewonden en gespannen, de muziek dreunt met een ondertoon van sacraliteit en uitdaging, dan weer snel dan weer eng langzaam en dreigend. Ik vergeet dat ik na uren langs de kant bijna niet meer op mijn benen kan staan. Een acteur krijgt het te kwaad en werpt zich met geweld tegen de mensen die voor me staan. Hij valt in een spasme op de grond. Achter me begint een oudere vrouw te gillen, haar armen stijf in de lucht, totaal hysterisch, en wordt in bedwang gehouden door drie mannen. Het hek is van de dam, overal schreeuwen mensen.

Het hoogtepunt nadert. In een rij gezeten op straat nemen een vijftal priesters plaats, en bereiden een offer voor op rieten dienbladen belegd met pisangblad, flessen arak en wederom bundels welige wierook. Vakkundig wordt het biggetje door vier priesters de keel door gesneden, en nog happend naar lucht ligt het kopje op een offerschaal, zijn pootjes achter de oren. Veel wijwater wordt er gesprenkeld en wierookdamp slingert alle kanten op. Vanuit haar hoger gelegen stellage daalt de heks in eigen gedaante, Rangda, met het meest heilige masker op, langzaam van de trap af naar beneden. De sfeer slaat om in paniek en angst. Ik krijg een raar gevoel in mijn buik, alsof ik misselijk ga worden en kijk Francis even aan. Hem vergaat inmiddels ook het lachen. De spanning ligt als en deken over het publiek heen.

Door wierooknevels zie ik nog dat er een bijkans totale psychose losbreekt. Er liggen inmiddels zo'n twintig mannen te stuiptrekken op het asfalt, het schuim op de lippen. De oude vrouw achter mij krijst, het ene na het andere meisje die het te kwaad krijgt, wordt direct naar de tempel gebracht. Ze worden maar niet 'wakker' uit hun trance, het heilige wijwater van de priesters ten spijt.

Het toneel staat inmiddels tjokvol mensen. Tegenover Rangda staat de Barong, een levensgrote draak, gespeeld door twee mannen. De Barong vertegenwoordigt het goede, de tegenpool van Rangda de heks en doet denken aan de draak die wordt meegevoerd tijdens de Chinese nieuwjaarsvieringen. Vergezeld van alle in trance geraakt mannen wordt een aanval uitgevoerd op de heks. Ze maakt stuipbewegingen terwijl ze een bizarre dans uitvoert, voorover gebogen beweegt de heks haar armen dreigend naar de grond en prevelt donkere woorden. Krissen zwaaien door de lucht, en plotseling staan alle behekste mannen op en wijzen met hun heilige wapen woedend naar de heks die gedurende tien minuten van alle kanten woest wordt bestookt met dolksteken. De acteur die Rangda leven geeft moet worden bevrijd van het heilige masker, want dat zou stuk gaan in de verdrukking. Een massale aanval vindt plaats, zelfs de sjamaan biedt zich aan en nodigt de razende mannen uit om zich met hun krissen op hem te storten. De oude vrouw achter mij krijgt het te kwaad en valt gillend flauw.

Het spektakel eindigt net zo abrupt als het is begonnen. De man die de heks speelt krijgt een lading heilig water over zich heen en doet zijn 'kogelvrije' vest uit. De spelers keren naar de tempel terug. De in trance geraakte mannen worden stuk voor stuk op hun voeten geholpen door priesters en potig uitziende helpers. Niet iedereen komt echter zo vlot bij zijn positieven. De paar mannen die niet zelf kunnen lopen, worden kreunend en stuiptrekkend weggesleept, ijlend en nog half in een stijve spasme. Een priester tilt een man op en rukt hem een paar keer onder de armen op en neer: wakker worden joh, kom op, 't is gedaan! De lichten gaan weer aan, en de menigte valt uit elkaar. De klanken van de gamelan ebben weg en de sfeer van wilde hysterie is plotsklaps uitgeraasd.

Terwijl ik over mijn pijnlijke middenrif wrijf, slenter ik tegen twee uur 's nachts met een wat witjes uitziende Francis terug naar het paleis. Onze begeleider staat glimlachend naast ons. Of we die honderd meter willen worden begeleid, vraagt hij. Nee, dat hoeft niet, met zijn tweetjes lukt het ook om terug te keren, zegt Francis tegen de paleisbewoner. Je weet het toch maar nooit, als eenling in de nacht, met dat spook in die boom. Ik huiver, en vraag me stilletjes af of het goede het kwade nou heeft verwonnen, of andersom...

Source

Archipel Magazine, Autumn 2009 (Dutch) eastmagazine.nl/ (originally: Archipel Magazine)