Oiassu, Roman settlement (80 BC-476 AD)

Below article is a description of the Roman era at Gipuzkoa in general, and more in detail of Oiassu (Irún, 10km east of San Sebastián/Donostia, Basque Country, Spain). The text is taken from publication in Basque Language called 'Erromatar Garaia' (p.105-115), issued by the Oiassu Museum (visit August 2017), downloadable from its website (see sources below).

The reason this article is published here is that it is now searchable online, and adds a wealth of knowledge on the Roman period in Gipuzkoa generally, and Oiassu in particular.

Image above: The Oiassu Museum (G.Dijkman, August 2017)

The Roman era: the encounter

The first true signs of Roman settlement in Gipuzkoa appeared a little over two thousand years ago, at about the beginning of the Christian era. They had been preceded by a series of military events, beginning with the initial disputes between Romans and Carthaginians for control of the Iberian Peninsula and concluding with the eventual inclusion of Gipuzkoa within the Roman orbit, as the result of advances from the Ebro Valley, Aquitania and the Cantabrian region.

The Carthaginian general Hasdrubal and his armies are reported to have marched into Gaul en route to Italy in 208 or 207 B.C., crossing the Pyrenees in the west “near the Ocean”, according to Titus Livius and Appianus. After the defeat of the Carthaginians, Roman generals undertook the conquest of Hispania, a territory which in the course of time they brought under their dominion.

Quintus Sertorius, governor of Hispania Citerior, remained loyal to his superior Caius Marius during the latter’s struggle against Pompey Magnus, rising up against Rome with the support of several local tribes from the valley of the Ebro, in the so-called Sertorian Wars, waged between 77 and 72 B.C. In 75 B.C. Pompey arrived in Hispania to do battle with the rebel, but finding himself short of provisions, retreated into the lands of Vasconia and that same winter founded the city of Pompeopolis (Pamplona).

Julius Caesar subdued the Gauls, killing over a million people in the process, according to Pliny, who disapproved of the conqueror’s methods. In 56 B.C. one of Caesar’s generals, Publius Crassus, did battle with the Aquitanians, who sought help from their Peninsular neighbours. The coalition was defeated and after the battle the greater part of Aquitania surrendered to the Roman.

Finally Octavius Augustus came in person to bring to heel the last outpost of resistance in Iberia. He launched land and sea attacks on the Cantabrians, finally subduing them in 19 B.C., and subsequently took shrewd advantage of the triumph for his own propaganda interests. Pax Romana had come to Gipuzkoa.

During this two-century long period the local inhabitants gradually began to emerge from their anonymity. Contemporary Roman chroniclers remarked on their uncivilised customs, the simplicity of their lifestyle and their warlike nature, clearly seeking to emphasise the beneficial effect of Roman influence on this savage and uncultured race. They attributed the wildness of the local people to the hostile climate and remoteness of the region.

The natives were said to live off acorns for most of the year, to have scarcely any wine and to drink beer. Their dress was simple, at celebrations they ate in communal groups, they used rudimentary boats and their rites of worship were primitive. Nevertheless, reference is also made to a road stretching from Tarragona on the Mediterranean coast to the last coastal Vascon settlements at Irun. Later on, in the middle of the first century A.D., sources referred to Vascon, Vardul and Caristian tribes living in the region which is now the province of Gipuzkoa.

The Pre-Roman Scenario

Over the last twenty years, archaeological research into the period prior to the Romans’ arrival in Gipuzkoa has yielded important new findings. Two distinct and contemporaneous cultures have been identified (Peñalver, 2001); one has its expression in cromlechs – stone circles with a funerary function – while the other manifests itself in hill-forts (castros). The cromlech region begins in the Leizaran Valley, running eastward along the foothills of the Pyrenees as far as Andorra, in a strip of mountain-land between 5 and 40 kilometres wide. This area is thought to have belonged to a distinct group who, on the basis of the geographical evidence, would appear to have been the Vascons.

The Leizaran borderline lies close to the tribe’s westerly territorial limit described by contemporary geographers. Fortified settlements, on the other hand, are found in the area adjoining the cromlech area, in Gipuzkoa (Intxur in Albiztur, Buruntza in Andoain, Basagain in Billabona, Muñoandi in AzkoitiaAzpeitia, Murugain in Aretxabaleta-Arrasate-Aramaiona, and so on) as well as in Navarre, Labourd, Lower Navarre and Soule. These were large-scale permanent settlements; indeed, the hill-fort at Intxur occupies one of the largest areas of any settlement of its time. They were located at strategic sites and equipped for defence with walls and great fosses; inside the fortified area stood dwellings, inhabited by people who engaged in arable and livestock farming and who had knowledge of ironworking. Amongst their hoards have been found certain articles characteristic of the Celtiberian world, although never in large numbers. In this same “Celtic” context we may also include a burial stele discovered in Meagas which shares features with objects found along the coast of Bizkaia.

The people do not appear to have been as isolated or uncultured as contemporary sources claim, but geographically they do appear to have been distributed along the general lines given in Roman writers’ descriptions. Gipuzkoa at this time was a crossroads between several cultures: Aquitania, the Ebro valley, and the Pyrenean and Cantabrian mountain ranges. The Bidasoa River marked the boundary with the peoples of Aquitania and also the northernmost limit of the cromlech region of the Vascons, which extended south and west to the Leizaran Valley and east along the Pyrenees; the area is bordered by the fortified settlements, which we may assume had connections with the Celtiberian world to the south. To the west, the River Deba separated the Varduls from the Caristians, whose lands stretched as far as the Nervion river. These two groups occupied territories that extended further south into the modern-day province of Alava. Roman texts referred to the various settlers of modern-day Gipuzkoa as Vascons, Varduls and Caristians, and it is by these names that they are known to history.

Image above: wooden maquette of the port of Oiassu (photograph: G.Dijkman, August 2017)

Maquette: a scale model

This scale model is a mere hypothetical approximation on what Oiassu looked like, used by the Arkeolan team. One of the tasks of archaeological work is to welcome new contributions, revisions and changes, so the scale model could be updated and serve to share the results of new findings with researchers.

In the process of reconstructing the relief of Oiassu, the following items were taken as reference: topographic plans, documents on the process of colonization and urbanization of the tideland marshes, cartographic sources and geological observations.

Based on this information, it was concluded that the hill on which the city was found, was the result of sediment accumulation brought by the Bidasoa river during the Ice Age. Up to recent times, this elevation was a peninsula, surrounded by the waters of the estuary to the north, east and west.

The limits of the urban space were adjusted to the esplanade area between the Casa Consistorial and he extreme north of the Beraun hill. This rather horizontal plane changed with the opening of the streets around Paseo de Colón, Iglesia, Fermín Calbetón, etc. This reticulated urban arrangement is inferred by a number of known buildings, squarely positioned in relation to the cardinal points.

Maqueta

Esta maqueta es sólo una aproximación, una hipótesis sobre la apariencia de Oiassu con la que trabaja el equipo de Arkeolan. Como la tarea arqueológica está abierta a nuevas aportaciones, revisiones y cambios, la maqueta se podría ir actualizando y serviría para compartir con los investigadores los resultados de los descubrimientos. A la hora de reconstruir el relieve de Oiassu se han tomado como referencias planos topográficos, documentos sobre el proceso de colonización y urbanización de las marismas, fuentes cartográficas y observaciones geológicas. De estas informaciones se desprende que el altozano sobre el que se asentó la ciudad es resultado de acumulaciones de sedimentos aportados por el río Bidasoa durante las glaciaciones. Hasta hace tiempos recientes esa elevación ha sido una península, rodeada por las aguas del estuario en los lados norte, este y oeste. Los límites del espacio urbano se han ajustado a la superficie explanada que se detecta entre la Casa Consistorial y el extremo norte de la colina de Beraun. Este plano, muy horizontal, se alteró con la apertura de las calles Paseo de Colón, Iglesia, Fermín Calbetón, etc. La ordenación urbana reticular se deduce de algunos edificios reconocidos, que se presentan escuadrados y orientados con respeto a los puntos cardinales.

Time line: The First Influences: 80 B.C. 10 B.C.

During the first century B.C. Gipuzkoa gradually fell under Roman sway, and the evidence indicates that the initial influence increased to a point where the territory had become part of the Roman order by the end of the century.

During the period of the Sertorian skirmishes a number of silver coins, which must have represented a small fortune at the time, were hidden in a cave at Usategi in Ataun. The trove consists of eight Iberian denarii minted in the native cities of Baskunes (a mint which has been identified as being in Vascon territory or Pamplona), Turiasu (Tarazona) and Segobrices (Cabeza del Griego, Cuenca). They all follow the same design, bearing a face with its hair in ringlets on the obverse and a mounted horseman on the reverse. They reflect the new trading customs introduced with Roman conquest, although native attributes are maintained. The Ataun trove points to the existence of trade with the Ebro valley, and is the earliest evidence of Roman influence in Gipuzkoa.

The Augustan coin discovered in the excavations at Beraketa Street in Irun can be dated to about 10 (12 – 6 A.D.). Nearby, in the environs of the parish church of the Virgin of Juncal other finds from the Augustan age have been made, amongst them several articles of crockery baked in Italic potteries. These mark the beginnings of a series of material changes which would transform the life of the most important population centres, in which the urban model developed and implanted by Rome throughout the territory it controlled would be repeated.

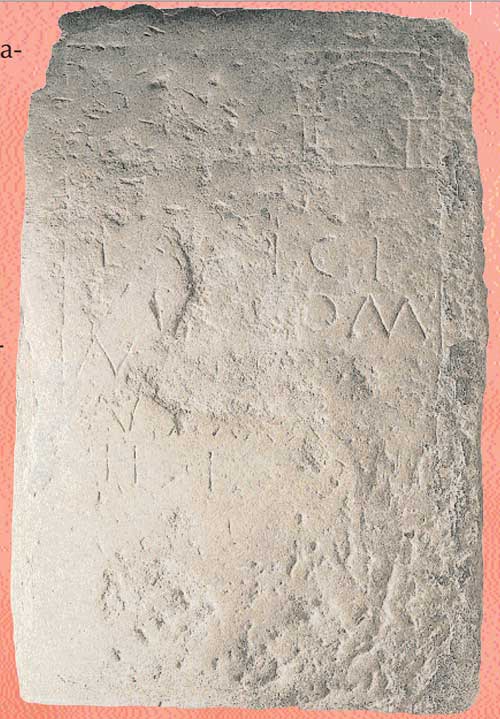

Image above: Stele of Andrearriaga, Irun-Oiartzun (photograph by G.Dijkman, San Telmo Museum, August 2017)

Oiassu Museum: Funerary stele featuring two persons, of whom one on horseback. Below, there is an inscription: VALBELTESO / NIS, indicating the name of the deceased. His name was Valerius Beltesonis (Valerius, son of Belteson), a Latin name followed by its Aquitaine of Basque filiation. Mid I century AD; Reproduction, scale 1:1. Original at San Telmo Museum, Donostia - San Sebastián.

Oiassu Museum: Estela de Andrearriaga (Irun-Oiartzun) Estela funeraria con representación de dos personajes, uno de ellos a caballo. Bajo ellos una inscripción: VALBELTESO / NIS, que corresponde al nombre del difunto; se llamaba Valerius Beltesonis (Valerio, hijo de Belteson), un nombre latino seguido de su filiación aquitana o vascona. Mediados del siglo I después de Cristo; Reproducción, escala 1:1. Original en el Museo San Telmo, Donostia - San Sebastián.

San Telmo Museum: This is a stele that crudely represents the figure of one man on horseback and another on foot, bearing the inscription VAL-BELTESONIS. This is interpreted as referring to Val(erius), a Latin name, and Beltesonis, a surname of proto-Basque or Aquitanian origin. It is considered to be an example of the relations existing at that time between the native population and the Romans.

San Telmo Museum: La estela de Andrearriaga (Oiartzun) tiene carácter funerario y está dedicada a un tal Valerio Beltesonis. Presenta un grabado tosco que dibuja una figura humana a caballo y otra a pie al lado. El difunto tenía nombre romano y apellido indígena, lo que denota una fase de transición en el proceso de integración en el mundo romano.

As clear evidence of a series of transformations taking place at the beginning of the Christian era we may cite the stele of Andrearriaga, a standing stone which has marked the municipal boundary between the towns of Oiartzun and Irun since at least the fifteenth century. This burial stele makes reference to a personage who adopted a common Latin name but it also includes reference to his native forbears: Valerius, son of Belteson, demonstrating the link between the pre-Roman culture and the new Latin or Roman practices.

The Upsurge: 10 B.C. 70 A.D.

Coinciding with the subjugation of the Cantabrian tribes a gradual but continuous increase in Roman culture can be observed in the Bidasoa estuary. There is evidence to suggest that this was the result of military actions undertaken from the northern side of the Pyrenees, linked to an Aquitanian focus of influence and probably to the military camp of Saint-Jean-le-Vieux at Donibani Garazi (Saint Jean Pied de Port). The focus of Roman interest seems to have to have been the silver mines of the Aiako Harria area, which are contemporaneous with the alluvial gold works of the Errobi River, the mines of Itchassou in Labourd, and the silver mines in Aldudes. These mines probably concentrated on the extraction of precious metals, necessitating complex planning and a sizeable work-force to undertake the large-scale movements of earth required. Supplies probably came from the port of Bordeaux, from whence were distributed the products of the Garonne basin, including crockery from the pottery works of Montans.

Evidence of crockery from Montans in the Bidasoa ceases abruptly after 70 A.D., to be replaced by articles from La Rioja. This change in the provenance of the pottery, denoting a change in the centres of influence which shifted towards the Ebro valley, was accompanied by other historical events whose consequences extended beyond the Bidasoa and the Gipuzkoan coastal area.

The Years of Prosperity: 70 – 190 A.D.

Since the very origins of the city, the history of Rome had been marked by conspiracies, assassinations and brutality, all used as means of achieving power. With the inception of the Empire in the time of Augustus all manner of intrigues were hatched in order to ensure the continuity of family candidates in the imperial succession. Tiberius was affected for life by having had to divorce his first wife, whom he loved, in order to marry Augustus’ daughter. Caligula’s insanity can be explained by the murder of his brothers and the death of his mother, exiled to the Isle of Pandataria on Tiberius’ orders and left there to die of hunger. Claudius was only proclaimed emperor because he happened to be found hiding behind a palace curtain by the Praetorian Guard, just when they were looking for a successor to the imperial throne to prevent the restoration of the Republic in the wake of Caligula’s excesses. Nero was another emperor whose insanity may be traced back to childhood traumas (when he was three he lost his father and was separated from his mother). The Senate declared him a public enemy and decreed his death, but he committed suicide with the aid of his secretary. Thus the Julio-Claudian dynasty founded by Augustus came to an end. After a civil war lasting just under a year Vespasian was elected with the support of the eastern legions. Already 60 years old when he was crowned emperor, he ruled for ten years; his sons Titus and Domitian, in that order, succeeded him, making up what is known as the Flavian Dynasty.

To Vespasian are due the initiatives which favoured the commercial and economic development from which the Basque coast and Atlantic territories benefited. Although the conquest of Britannia had begun during the reign of Claudius, under Vespasian the Roman fleet reached Scotland. In 73 –74 A.D. Vespasian granted Latin law to all of Hispania. Under this new jurisdiction, which was implemented in stages, those who held public office in municipal administration gained Roman citizenship, a concession which favoured the development of cities. As a result of this new state of affairs Roman interests in Gipuzkoa were refocused: the port of Oiasso (Irun) was expanded, ceasing to be merely an economic centre for silver mining and accruing other more important functions to become a regional port for the Bay of Biscay. Indeed, such transition was a standard feature of Roman expansion: the economy of newly-conquered territories developed from the simple exploitation of natural resources as a means of meeting occupation expenses to the generation of surpluses and the transformation of production structures.

In 97 A.D. the Senate named Nerva emperor. The new dynasty, the Antonine, which came to power in 97 A.D. and lasted until 192 A.D., oversaw the zenith of Rome’s greatness, although by the end of the period a crisis had begun which would fully erupt in the third century, ushering in the period of decline.

Throughout all these years the civitas of Oiasso retained its vigour, trading over a wide area which included the lands on the left bank of the Garonne, the middle valley of the Ebro, the western slopes of the Pyrenees and along a coastal stretch running approximately from Bordeaux and Santander. Long-distance trade was also engaged in, if only sporadically, and imports are documented from the Eastern Mediterranean, Andalusia and the Gulf of Narbonne. The rest of the Gipuzkoan coast seems also to have benefited from this favourable state of affairs, as indeed did the hinterland, as the finds at Eskoriatza and Urbia prove.

Decline and Decadence, 190 – 305 A.D.

After emerging victorious from the civil war, Septimius Severus founded the dynasty of the Severi, which included his sons Caracalla and Geta and other emperors up to Severus Alexander. Caracalla extended Roman citizenship to all inhabitants of the Empire 212 A.D. The subsequent period of rioting, known as the “military anarchy”, lasted almost until the end of the century. One emperor after another was appointed by the armies until Diocletian, of humble origin, succeeded in reorganising the government and holding power for over twenty years. However, the decline was by now irreversible and the break-up of imperial territories, the problems with the Barbarian tribes and the Christian movement would together undermine the Roman system to the point of rendering it unrecognisable. Hispania became a diocese dependant on the Prefecture of Gaul. Juliobriga (Reinosa), Veleia (Iruña de Oca) and Lapurdum (Bayonne) each became the seat of a cohort tribune, a high-ranking military officer, and were equipped with important defensive fortifications. Products from the North of Africa still reached the port of Oiasso, but trade gradually dwindled to a trickle.

The Late Empire: 305-476 A.D.

Emperor Constantine legalised Christian worship in 312, while Theodosius elevated it to the status of state religion in 380. It was during the latter’s reign that the Goths were allowed to settle within the imperial boundaries, between the Balkans and the Danube, in return for safeguarding the Danube-limes; the bishops proclaimed the superiority of religious over imperial authority and went so far as to excommunicate the emperor himself; finally, the empire was divided between the emperor’s two sons – the East going to Arcadius and the West to Honorius. After the division Vandals, Alani and Ostrogoths invaded the western empire and the Gothic chieftain Alaricus seized the opportunity to lay siege to Milan and advance as far as Rome. A fresh invasion took place on New Year’s Eve, 406; with the Rhine frozen over, Vandals, Suevi and Alani crossed over to the west, succeeding in reaching the Pyrenees and entering Hispania. One by one, the empire lost its territories until only Italy remained in imperial hands. Even here, in September 476, during the reign of Romulus Augustulus, Odoacer, an officer of the imperial guard and son of a Barbarian king, managed to persuade the troops of the last Roman navy to mutiny and proclaim him emperor.

These changes are reflected in the archaeological evidence collected in Gipuzkoa. The thriving Oiasso of the first and second centuries shows scarcely any sign of economic activity in this later period. The quays of its port appear to have fallen idle, its hot baths to have been used for stabling livestock, and the memorials in its cemetery to have been allowed to fall into ruin. Getaria too, seems to have been deserted. In contrast, there is evidence of a significant return to cave-dwelling, possibly on account of a resurgence in livestock herding. The saltmine of Dorleta in Leintz-Gatzaga and the ironworks on the hill of Arbium in Zarautz are the only two production centres which are known to have been in use at this time. Coins and decorated crockery unearthed from this period contain Christian symbols, evidence of the prevalence of the new religious movement.

The abrupt break with Rome from the fifth century onwards is surprising. The geography of the area made it vulnerable to Barbarian attacks: it lay close to major communication routes – especially the crossing of the Pyrenees – and was easily accessible from the sea. In 428 Aquitania surrendered to the Goths; in 449 Rechiarius, king of the Suevi, sacked Vasconia; in 445 Herulian ships attacked the coastal area inhabited by the Cantabrians and the Varduls; in 473, the Gothic count Gauderius entered the area through Pamplona and conquered Saragossa and its neighbouring cities.

Roman geography of Gipuzkoa

Although contemporary references do not abound (Strabo, Pliny, Pomponius, Mela and Ptolemy are the most important) they do tell us the names of some of the most important settlements. The most prominent was the coastal polis (civitas or city) of Oiasso, in the dominions of the Vascons, which stood at the end of the Roman road leading from Tarraco (Tarragona). Further west, in Vardul territory, were the oppida (fortified areas) of Morogi, Menosca (next to the River Menlakou) and Vesperies, and the polis of Tritium Tuboricum. Beyond these, the River Deba marked the boundary between Varduls and Caristians. Of all these settlements the only one which has been positively identified is Oiasso in Irun, the Vascon tribe’s only outlet to the sea from their lands which stretched back towards the Pyrenees. Any of the castros discovered in recent years might mark the site of one of the oppida, while the only evidence we have for the site of Tritium Tuboricum, which is thought to have been on the banks of the River Deba, is phonetic, linking it to the present-day town of Mutriku.

The juridical conventi – or administrative boundaries of Clunia and Caesar Augusta met in Gipuzkoan territory. The notion of the conventus had existed since the time of Caesar, but it was defined and fixed during Claudius’ reign. It comprised an administrative, political, juridical and religious unit. These conventi lost their raison d’être after the reforms of Diocletian about 288. Varduls and Caristians were governed by the conventus of Clunia (Coruña del Conde, Burgos), while the Vascons were included in the conventus of Caesar Augusta (Saragossa). Both formed part of the province of Tarraconensis, Augustus’ new name for the former province of Hispania Citerior.

Archaeological evidence has added considerably to our information on Roman Gipuzkoa and in recent years a fair number of settlements have come to light. Excavations at the hill of Arbium, overlooking the inlet of Zarautz, show the existence of human occupation linked to the iron industry which developed in the fourth century and which was in some way related to the finds at Getaria belonging to an earlier age, which will be dealt with below. The town centre of Zarautz itself, where Roman coins and other remains have been discovered, was also inhabited during this era. Nearby, in the neighbourhood of Elkano, a new find has recently been made. Like the hill of Arbium, the hoards include no imported objects, evidencing an unsophisticated material culture. At the southern end of Gipuzkoa are the finds at Urbia and Leniz. In the former, several open-air constructions have been found, dating from the early imperial period (the first and second centuries) and related to herding practices in the area. Indeed, the valley of Urbia, which stands over 1,000 metres above sea level at the foot of the Aizkorri mountain range, is inhospitable for all but seasonal occupation.

The stone altar of Oltza, said to have been brought from Zalduendo to form part of the structure of a shepherd’s dwelling, may well be related to the finds at Urbia and Leniz. It certainly appears clear that there was a connection between this area and the Plain of Alava, and specifically the city of Alba in San Román de San Millán. In the area in and around the watershed and close to the boundary with Alava Roman tanks have also been found, which would have been associated with the salt-springs of Leintz-Gatzaga. Although there are reports of an Iberian denarius coin being discovered in this area, the hoards found by archaeologists are not as old, dating from the fourth or fifth centuries and even later. From this same borderland area there are old reports of coins being unearthed at Idiazabal and Ataun, as well as a gold ring engraved with the imperial eagle found at the Jentilbaratza fort in Ataun (the ring was most likely a composite piece, with a stone cut in Roman times set in a mediaeval gold mounting). More recently, in 1986, a funerary inscription was discovered at the chapel of San Pedro de Zagama, alongside an ancient access route to the Aizkorri mountain range.

The fact that the evidence of cave-dwellings at Jentiletxeta II (Mutriku), Ermittia (Deba), Ekain IV (Deba), Amalda (Zestoa), Anton Koba (Oñati), Aitzgain (Oñati), Sastarri IV (Ataun) and Iruaxpe III (Aretxabaleta) dates from the fourth and fifth centuries, (i.e. the end of the period) is revealing. Cave occupation at this time is characteristic not only of Gipuzkoa but is frequently found in other regions, both nearby (Navarre, Alava, Bizkaia and La Rioja), and further afield. Such a widespread phenomenon has given rise to several theories: some hold that the caves were occasional shelters used in times of trouble; others that they were used by herdsmen or had some religious significance.

Roman objects are also being unearthed in town centres; first in Eskoriatza in 1982, and subsequently in Donostia-San Sebastián and Tolosa. Generally they are found outside their original context, forming part of deposits belonging to more modern periods of occupation.

By way of summary, the Roman remains discovered to date in Gipuzkoa have largely been found at the edges of the province. There is a concentration of remains along the coast of the Bay of Biscay, as a consequence of offshore traffic. Another point of concentration lies further south in the vicinity of the watershed connecting Gipuzkoa to the Plain of Alava and the Burunda Valley, through which the route from Pamplona to Briviesca passed. However, the greatest density is found in the Bidasoa Estuary round about the civitas of Oiasso. In any event, even on the basis of the evidence to hand, Gipuzkoa contained two polis and three oppida in addition to a considerable number of other settlements. This is a significant total: given the small size of the province and the likelihood of further finds in the future the picture to emerge is that of an unexceptional region of the empire. Only in one aspect is it unusual: the relative absence of epigraphs, only two of which have been found to date.

The transformations

The Romans’ interest in Gipuzkoa may have been limited to its mineral resources, the troops and taxes it supplied and its strategic position on land and sea routes, but Roman rule brought substantial changes to the way of life of many local people, especially where urban lifestyles were adopted. Indeed, the city was the most important vehicle for transmitting Roman models: in it were concentrated the functions which allowed the new administrative network to prosper. Researchers agree that natives of the northern regions of Iberia who enlisted as legionnaires contributed to the development of urban life in their birthplaces when they returned after the mandatory twenty-five years of service. Bearing in mind the sizeable number of Vardul and Vascon soldiers amongst the troops stationed in Britannia and along the Rhine, it is quite possible that they played a leading role in consolidating urban environments in the area.

The application of the Roman urban model brought about changes in architecture, street-plans, economic activity and in the mentality of the people themselves.

In architecture, more extensive use was made of bricks and roof tiles, concrete and special mortars. New forms appeared, such as the vault and the arch. Improvements were made to timber construction, which was widely used, while stone was employed for important or emblematic buildings. There were also changes in the ironwork used in building (with the manufacture of new nails and bolts) and in methods of reinforcement and finishing. Labourers had to acquire the skills required for the new systems and suppliers of raw materials, traders and transporters were also needed.

Rectilinear street systems evolved around main roads, squares and other public areas and the concept of building lots was developed. The urban area was delimited by a fence or wall, which marked out a special area with its own privileges. Over time, it became necessary to fortify these symbolic limits against incursion and attack. A main roads passing through a town became its high street and was generally paved in stone. Outside the road also played a dynamic role, acting as a focus for the poorer quarters when the population grew too large to fit inside the city walls and as a reference point for building cemeteries. The forum, a rectangular open area flanked by buildings, was the main venue for public events and ceremonies, as well as acting as a market and meeting place.

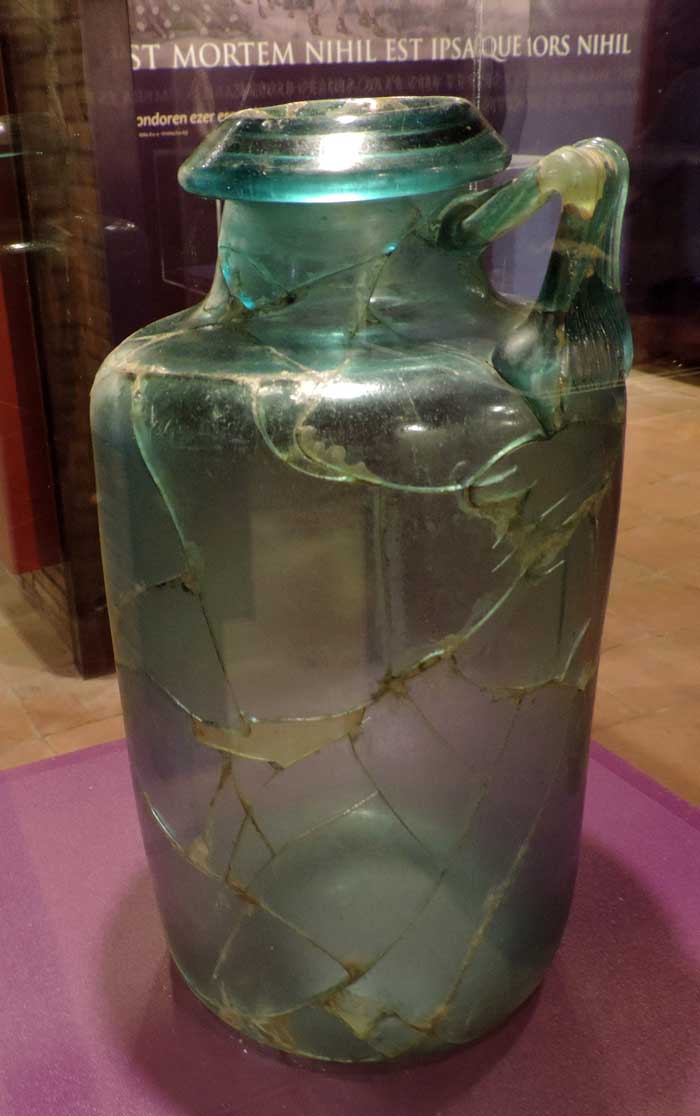

Image above: Sophisticated vessels were used for important burials. Glass urn; Santa Elena (text: Oiassu Museum; photograph G.Dijkman August 2017)

Oiasso

The road from Tarraco (Tarragona) runs through Ilerda (Lerida) and Osca (Huesca) as far as the last Vascon towns on the coast of the Ocean, both in the region of Pompelon (Pamplona) and Oiason, a city situated on the very edge of the Ocean. The road measures 2,400 stadii and ends at the border between Aquitania and Iberia. Strabo, Book III, 4.10. (written between 29 and 7 B.C.).

The River Magrada embraces Oeason. Pomponius Mela, Book III,1.15. 43-44 A.D.

The breadth of the Iberian Peninsula from Tarragona to the coast of Oiarso is 307,000 paces... starting at the Pyrenees and following the shore along the Ocean we come to the forest (or mountain pass) of the Vascons, Olarso. Pliny the Elder. Natural History, Book III, 3. 29 and 30. (middle of the first century A.D.).

Amongst the Vascons: the city of Oiassó and the Oiassó promontory (Coordinates: 15o 10’, 45o 05’. 15o 10’, 45o 50’). Ptolemy, Geographia, II.6. (middle of the second century A.D.).

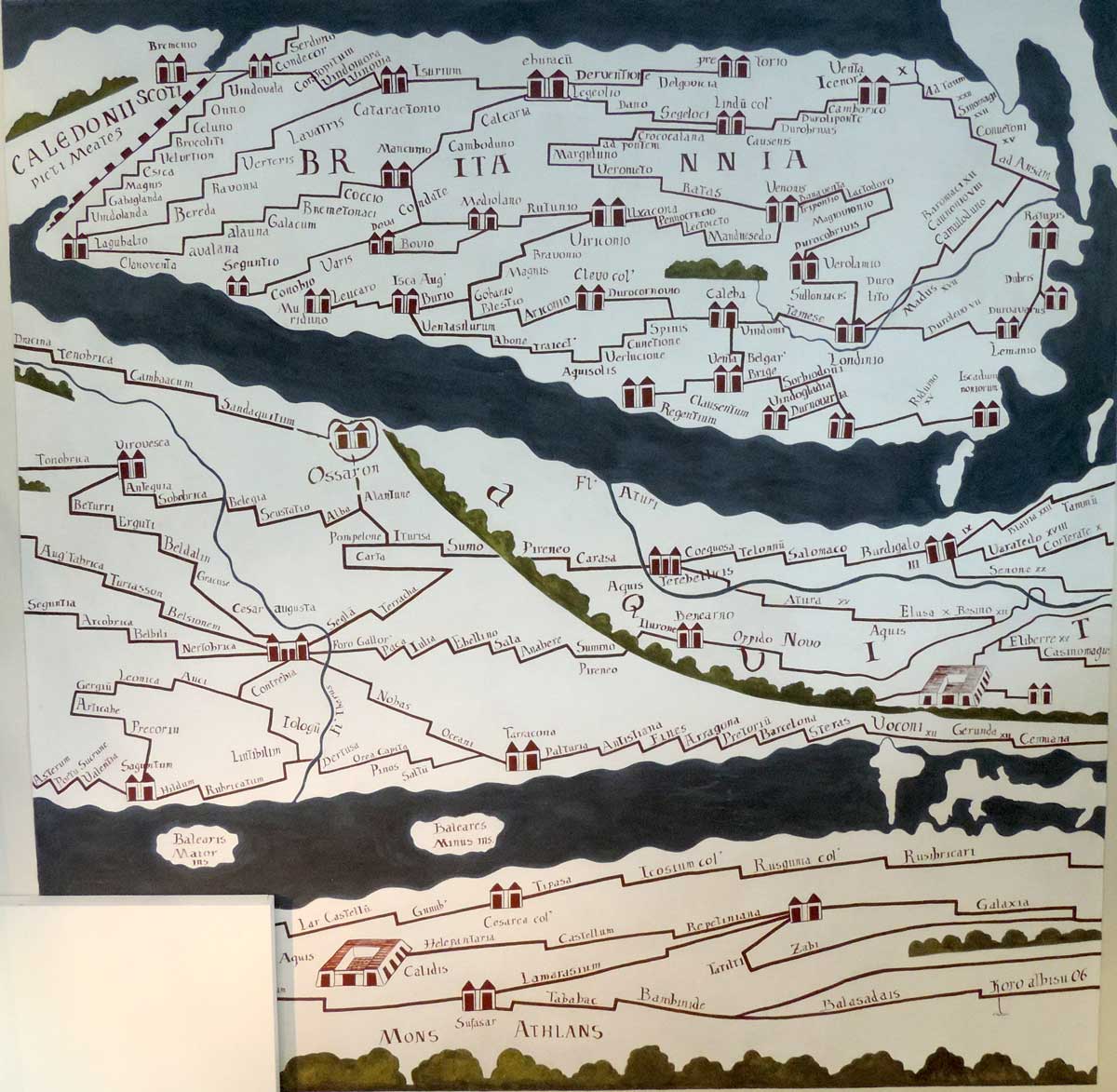

Image above: Museum Guide Item number 63. This map of the Roman organisation of the territory shows Oiasso (given as Ossaron) as a point where various roads met. It is also given a distinctive symbol representing a fortified settlement. The only other towns of this category in the region are Dax, Saragossa and Briviesca.

Present-day Irun is an international communications centre, a bridgehead connecting the Iberian Peninsula to the continent of Europe. The main railway line from Madrid, the narrow-gauge line running along the Cantabrian coast, the N-1 and N-240 national primary roads (from Madrid and Tarragona respectively), the N-634 which extends as far as Galicia, and the A-8 motorway from Bilbao and Santander, all meet here to cross the Bidasoa River and pass through Hendaye en route north to Bordeaux and Paris, and east to Toulouse with its multiple connections with the Mediterranean and the Rhone corridor, Switzerland, Germany and Italy. It is the most important crossing-point in the western Pyrenees and a natural pass used by migrating birds. Irun is, also the successor to Oiasso, the Vascon civitas.

This relationship is reflected in the name of the town (Iruña in Basque), like Pamplona (also Iruña) and the ancient city of Veleia, the third “Iruña” in the Basque Country. Irun-Iruña, together with the other Iliberris or Irunberris throughout Roman Hispania and Gaul (as far apart as Andalusia and Narbonne), was probably the generic term for an urban centre or city, to distinguish it from other population centres.

For many years Oiasso was thought to have been sited in modern-day Oiartzun, but the discoveries of the last thirty years have effectively put an end to this misnomer. Isolated discoveries were made in the 1960’s at the Higer headland and Juncal Square, followed shortly afterwards by the discovery of the Roman cemetery at the chapel of Santa Elena. Years later, in the eighties, remains of Roman mining were identified in the surrounding area. In the early 1990s, evidence of the city itself were found – remains of the hot baths and residential buildings. As far as is known, the Roman civitas was situated on a height in the historical town centre in the area between the Town Hall and the end of Beraun. It was surrounded for the most part by the waters of the estuary, beside which a thriving port developed.

Information gleaned from the excavations of the dock area in Santiago St and Tadeo Murgia St shows that the quays were built of timber, following the contour of the hillside in the area adjacent to the water. Ships could dock there at any tide and goods were unloaded and stored in quayside warehouses. Merchandise that had been spoiled during the voyage was thrown into the harbour alongside the jetty. Together with the dumping of urban waste in the same area, this practice finally rendered access to the quays by boat impossible. The urban settlement stretched over about fifteen hectares, presumably in a regular layout of streets, residential blocks, and public buildings and spaces.

The cemetery, at one of the main exits from the city, extended beyond the city limits. The area of influence of the civitas stretched at least along both sides of the estuary up to the river-mouth, and remains dating from this period have been found within the walled part of Hondarribia, in the area of Ondarraitz Beach (Hendaye), on San Marcial Mountain, on Jaizkibel and at the foot of the castle of San Telmo in the Bay of Higer. The inhabitants of Oiasso enjoyed a similar standard of living to that of other urban centres on the Atlantic; their diet, standards of hygiene, dress and leisure habits were all similar to those prescribed by Roman customs; they shared the same funeral rites and religious celebrations; they were familiar with written Latin; and they devoted themselves to trade and crafts, as well as mining, fishing and other pursuits related to the town’s strategic position in the communications network.

The remains of a bridge over the Bidasoa River have recently been discovered, confirming that this was a communications hub, linking Aquitania and Iberia, with all the traffic from the various highways and byways to the north and south converging at this bridge. The city was also an important port-of-call for coastal traffic between Burdigala (Bordeaux) and Santander. Oiasso’s age of splendour lasted from 70 to 150 A.D.

Urban life: Trade

The items traded in the Bidasoa area probably included preserved fish, wood, furs and silver, lead and iron ingots, as well as products obtained in the surrounding territories. This trade would have been in the hands of an urban merchant class whose members did not actually produce anything, limiting themselves instead to trading in commodities. The environment was favourable to business, with weights, measures and currency all being standardised throughout the empire. The containers, or amphorae, were also of standard sizes and shapes. At the same time, the city had a plentiful supply of glass-workers, ironsmiths, weavers, potters and other workers, both freemen and slaves, who concentrated on mass production for local and foreign markets.

There was also a large services sector, with domestic servants who carried drinking water, cooked, undertook repairs, sewed or worked in the garden. They all required basic foodstuffs which were not to be found in the city area, although they would have had some fruit trees, vegetable plots and animals for their own consumption. Commerce, as is shown, was one of the chief activities in Oiasso, which traded products at a regional level. The finds so far show that produce came from as far afield as the Ribera of Navarre, La Rioja, the Saintes district north of Bordeaux and from other regions linked to the river traffic of the Garonne.

Occasional merchandise arrived as a result of long-distance trade networks, as in the case of goods from Andalusia, the Gulf of Narbonne, the coasts of Italy, North Africa and even the eastern Mediterranean. Generally speaking, imports accounted for 30% of the port’s business, and its radius of activity centred on the Gulf of Biscay. As a seaport Oiasso would have served as a trade outlet for the inland regions between the left bank of the Garonne and the middle valley of the Ebro, thanks to the links between the port and the overland communications network through which trade was channelled along certain roads.

Crafts

Amongst the thousands of objects recovered during the excavations of the port of Oiasso are small pieces of ingots of raw glass. This material was mainly produced along the coasts of Asia Minor, owing to the quality of sand there, which had a high silica content. The sands were smelted down and left to set in big blocks which were then broken up and shipped to the West. Whatever the origin of the ingots discovered at Oiasso, they are clear evidence of the existence of local craftsmen who turned them into everyday objects like bottles, glasses, plates and phials. Although the glass-blowers’ workshops have not yet been found, they may be assumed to have worked some distance away from the urban area, at the edge of the city.

The proportion of glass articles in the stores of the townspeople is very high and includes a sizeable variety of kitchenware items. Several colours of glass have been found, ranging from whitish to dark, with a preponderance of iridescent blues and greens. The usual blowing and moulding techniques were used, although there is one exceptional piece of carved glass depicting the profile of the face of a femenine figure; it is still possible to make out a very fanciful hairstyle, the features of the face and even an earring on the ear-lobe.

There were most certainly ironsmiths in the town: excavations have brought to light utensils and even a stock of studs, stored in a pot. These items had been buried next to the foundations of a building, in the area now occupied by Beraketa St – one of the oldest streets in Irun – probably in the first century A.D. The reason for hiding them remains obscure. Amongst the tools were a file and a pair of small anvils for making nails and, next to these, over a hundred pieces of all shapes and sizes. The studs are short with large rounded heads, but there are also long nails with square-shaped heads which are thought to have been used for pinning construction beams together. The way in which they were made was probably as follows: the smith would draw out an iron bar in the forge, heating and shaping it until he had made thinner rods of approximately the size of the intended object. While the metal was still red-hot, he cut pieces off the rod of the size of nails or tacks and hammered one end to a point. The heads were made afterwards, by inserting the rods or pins into a hole in the anvil and hammering the other end flat.

The forge was the last link in the iron-working chain. The first stage involved “reducing” the iron to obtain rough ingots; these were then refined into compressed metal bars of uniform quality. The ironsmiths were responsible for transforming these bars into miscellaneous implements, from knives, spears and cow-bells to ploughs, rings and nails. They were also responsible for repairs.

Pottery is another craft associated with the Oiasso urban area. No kilns or workshops have yet been discovered; but studies of the thousands of fragments of vessels which have appeared to date all point in one direction. Aside from the imported articles, the items, for all their variety of form and finish, share a number of common features in terms of the make-up of the clay. This suggests a single supplier of raw material and a common clay-making and pottery tradition. Further evidence to support this theory comes from the way the pottery industry was organised at the time, with regional centres of production supplying specific areas. These production centres were usually situated in the most important towns in the area.

Daily Life

The widespread use of money payments and the standardisation of weights and measures are only two examples of the profound transformations that were taking place at the beginning of the Christian Era. The earlier self-sufficiency and subsistence models lost ground in an urban society based on regional and even international trade, as well as more local commerce. It is hardly surprising that the citizens who had been freed from the burden of producing their own food, and who were now devoted to obtaining resources for sustenance and profit, living in stable groupings and concentrated in a delimited space, should develop new ways of living together and relating to one another.

Bearing in mind that Latin law began to be implemented from the year 74 A.D. onwards, there must have been a municipal organisation. This would probably have been first and foremost concerned with administering justice, collecting taxes and maintaining the cult of the emperor. Since Oiasso was a border city between Aquitania and Tarraconense, there may also have been a portorium for levying tolls and transport taxes. The Roman economic system, of course, depended on a work-force of slaves to keep its productive sectors operative. Slaves were assigned the hardest tasks but were also given more usual occupations in the home, education and trade.

Dwellings were equipped with only the most basic furnishings. Cupboards, niches, paved floors and mural paintings were the main focal points, with furniture being confined to very basic items such as beds, chests, stools, lampstands and utensils for washing and heating. The kitchen was the best-equipped room. The most common utensils were ceramic vessels which were used for holding liquids, for cooking and serving food, for storage, as flowerpots and so on. One of the kitchens unearthed was equipped with typical utensils including pots, plates and bowls. The pot would have been used for cooking food, as can be seen by the fire-marks on the base and the fitting lids. Depending on its size, however, a pot could also be used for storage. The plate and bowl would have been used at table.

Other ranges have also been found, showing that all the most common models of plates, glasses, pots and jars were available in the civitas of Oiasso. There were also bouilloires, jars used for boiling water, probably to make herbal teas, and local amphorae. The highest quality articles, however, came from elsewhere. This is the case of the mortars used to prepare seasonings, which had to be particularly tough, and the baking dishes, which had to support high temperatures, and also of the tableware, the famous terra sigillata. Initially tableware from Montans was used but with the expansion of the Tricio workshops near Nájera, tableware from La Rioja took over the Oiasso market. It came to account for about 15% of all the pottery used in the city, and included a wide variety of plates, goblets, bowls and tumblers. There were other items too: tumblers and ‘finewalled’ goblets crafted from a very fine paste. The majority of these articles come from two sources – one to the north, on the far side of the mouth of the Garonne in the Saintes region and the other to the south-east, in the Ribera of Navarre.

Torches soaked in inflammable substances were used to light public places and dark streets and roads, and also in religious ceremonies. Inside the houses candles (candelae) and small oil lamps (lucernae) were used, either singly or in sets. Oil lamps are one of the most representative manifestations of Roman visual art, reflecting popular tastes. They combine the features of a basic low-cost product (they were mass produced in clay, using moulds), widespread use, fragility and a vehicle for decorative art. Oil lamps fitted in the palm of the hand but the surface area was large enough to accommodate drawings and figures. They could have floral or geometric patterns or figures of animals, busts of gods, battle scenes or erotic and other motifs, which would be chosen by the purchaser according to his tastes.

Diet

Thanks to the regional trade channelled through the seaport of Oiasso, oil, cereals and wine were a staple part of urban life. The usual suppliers were the vineyards of the Gironde (Bordeaux), the oil-producing region of the Ebro and the great granaries of the Adour, the Garonne and the Ebro. On occasion products from other areas were also available: the prized olive oil of Andalusia, wine from the Gulf of Rosas and – very exceptionally – products from the Eastern Mediterranean. There were, of course, local cereals and vineyards, and animal fats were used to supplement vegetable oils, but all these were for private consumption and were insufficient to meet the needs of the whole community. The everyday diet also included a great variety of fruits and berries, both fresh and dried, like figs, sloes, plums and prunes, cherries, morello cherries, grapes, olives, blueberries and peaches (the latter were very plentiful), and nuts such as walnuts, hazelnuts, beechnuts, acorns, pine-nuts and almonds. Many of these were native wild products from the beech and oak forests; others came from plantations introduced by the Romans, as was the case of walnuts, hazelnuts, plums, figs and cherries; yet others, like olives and almonds, pine-nuts and peaches, were imported.

Pork was the most common meat, though mutton, kid and beef were also eaten. Supervised herds of pigs would have been fattened up in the oak-forests surrounding the city; flocks of sheep were also kept, in other pastures. The hills encircling the city were safe summer pastures while in the winter the animals would have been taken to graze in coastal areas. It is reasonable to think that cattle were tended in a similar way, though some stabling may also have taken place. Indeed, the regular supply of milk and the evidence of farm-work would suggest that stables may even have been located in the urban area itself. Hens, chickens and cocks were all a standard feature of city life, as were dogs and horses. Hunting provided another source of meat, with the citizens eating venison, hare and fowl.

Fish and shellfish were also commonly eaten and vast numbers of oysters were consumed. This varied diet was completed with garden products: we have evidence of the cultivation of celery and strawberries, and of medicinal plants such as mint and vervain.

Dress

The evidence suggests that spinning, weaving and sewing were all common practices. Vegetable fibres such as linen and animal fibres such as wool were both used. The raw material was spun on metal spindles and fusaiolas, generally made of pottery. The cloth was then woven on wooden looms, of which vertical looms with weights, invented during the Bronze Age, were most common. Finally the cloth was cut up and hand-stitched with the aid of pins and thimbles. Belts, pins and clasps were used for fitting.

People wore the footwear typical of the Roman world. Most of the pieces recovered come from the underside of the shoe, and both fragments and intact soles have been found. There are remains of studded footwear, but it is impossible to determine whether they come from boots or sandals. There are also examples of stitched footwear, both pointed and rounded in shape.

Hairstyling was not merely a matter of enhancing personal appearance: its primary function was hygienic – well-groomed hair kept parasites at bay. Combs were carved from a single piece of wood, with rows of teeth extending out on either side from a central shaft. The teeth at one end were set very close together to aid delousing, while at the other end they were more widely spaced for grooming. Long hair was tied back with ribbons, braided or gathered into a bun which was held in place with a back comb, a metal hairpin or small needles fixed on a rounded head, called acus crinalis or ‘hair needles’, generally made of bone.

Jewellery was worn extensively. Bronze pendants were very common, as were gold pendants with openwork motifs, glass beads or stone or glass paste inlay. People wore bracelets (arnillae), necklaces (monilia) and chains (catena) from which they hung amulets, often associated with popular superstitions. They also wore rings (annuli), sometimes engraved with personal emblems or containing mounted engravings crafted with precious stones, bearing religious or allegorical motifs.

Standard of Living

Some of the items unearthed at the civitas of Oiasso suggest that local citizens enjoyed a high standard of living. Graffiti on clay vessels, consisting of lines drawn with a sharp object after the vessel was made, demonstrates that writing and use of the Latin alphabet were common among the inhabitants of the polis. Another important find consists of a cache of spoons and applicators used for preparing and applying ointments and powders. The spoons are very finely made, with a small bowl, and the applicators resemble cylindrical rods, except for one which may have been some kind of medical probe. Excavations have also unearthed a tessera. Tesserae were tokens, generally made of metal and shaped somewhat like coins. They were used as entrance tickets for theatres, hot baths and other public places, and also as counters in games, safe-conducts or receipts for payment of services, and probably for other functions which have not been identified.

Leisure

During their leisure time, children and adults alike played a wide variety of games, some of which have come down to us virtually unchanged. These included gymnastic sports, spinning tops, marbles, handball, noughts and crosses, knucklebones, odds and evens, heads-or-tails, dice and ludus latrunculorum, which was very popular amongst soldiers: this was a game of strategy played on a board and was akin to chess or draughts. Each player had 18 counters. However, the most popular games among adults were dice and knucklebones. These were not just pastimes: important amounts of money and other goods were staked on the result. Fair play was not always the order of the day – examples of weighted dice have been discovered from the period.

Ecology

Inevitably, all this change and transformation had an impact on the environment and ecology of the surrounding area, as more and more woodland was felled, new orchards were planted with imported species of trees and mining work created its own pollution. In itself the timber required for construction and as fuel in silver-mining and iron-working must have reduced the forest area significantly. The fruit plantations too must have altered the landscape considerably: many of the seeds found during the Oiasso excavations are the first of their species in the Iberian Peninsula. There is evidence of plum, fig and even cherry trees, indicating not only that these hitherto unknown species were introduced and grown in the area, but also that they underwent improvement and selection methods. There are surprisingly high concentrations of lead pollution in the deposits of the Bidasoa estuary associated with Roman habitation. These are a by-product of mining in the area and come from the waste and run-off water used in cleaning and sifting the ore to extract silver.

Mining

It has been calculated that it would have taken four hundred men working for two hundred years to dig the fifteen kilometres of Roman galleries at the Arditurri mine in Oiartzun. These figures may be too high, but there is no doubt that the local silver ore (argentiferous sulphide) was mined intensively during this period. The industry was not confined to Arditurri but also extended to other parts of Gipuzkoa. The archaeological evidence so far indicates that the entire area of Aiako Harria, from Bera de Bidasoa to Irun was worked intensely, and that there were also smaller mines in the areas surrounding Cinco Villas and Udala. As more information comes to light, it is quite possible that most of the many more recent mines in the area – none of which are still active – will prove to have been exploited by the Romans.

There are a number of features that are specific to Roman mines: the galleries are narrow and vaulted, the walls finished off with fine pick-work, and hollows have been left at regular distances for lamps. The floors are well cut and, where there is a slope, stepped to facilitate transport. They are easily distinguished from later, less carefully-built works. Dozens of examples have so far been catalogued, giving us a good idea of planning and working conditions.

In order to locate seams of ore, the Romans first observed the vegetation and surface. They then dug steep shafts down through the upper strata until the vein was met. If no seam was discovered, or if it contained insufficient ore, the shaft was abandoned. If it was judged to be workable, however, a horizontal gallery was then dug for the purpose of extracting the ore and bringing it to the surface. If the seam was big enough, several additional galleries might be built. Where possible the use of shoring-timbers was avoided, as these required that some parts of the seam be left unmined.

The method used for boring the galleries is known as fire-setting was to remain unchanged until the invention of explosives. Wood fires were lit next to the rock, which heated and fractured. A pick-axe was then used to pull out the rock and shape the gallery.

The ore was cleansed of impurities and ground down to select the particles with the highest purity. It was then sifted in pools of water. Smelting was carried out near the mine. Because sulphide is essentially lead with a high silver content, the first smelting process produced a substance in which both lead and silver were still mixed. In a second stage, known as cupellation, the silver was separated from the lead.

We known nothing about the status of the miners; whether they were freemen, serfs or slaves, or whether they were under army control or worked for companies which had obtained mining rights from the state. Archaeological hoards found inside the mines suggest that Aiako Harria was already being mined during the reign of Augustus and that intensive work continued throughout the first century A.D. Subsequently, production may have fallen off or even been abandoned altogether as a result of competition from other more profitable mines. In any case the mines lay forgotten until their rediscovery at the end of the eighteenth century by a German engineer called Johann Wilhelm Thalacker, who had been called in by the Sein family of Oiartzun to resume mining at Arditurri.

Thalacker was familiar with the majority of Roman mines in the Iberian Peninsula and in a report published in 1802 he described the features of the galleries, which he considered comparable to those at Cartagena, Leon and Rio Tinto. His report was used extensively by mine-owners seeking mining rights at the end of the nineteenth century who used the original Roman mines to reach previously unworked seams. Unfortunately, this required widening the galleries, which effectively destroyed all ancient remains. In addition, the lead rubble discarded by the Romans was found to contain sufficiently high traces of silver to make it viable to transport it to a new smelter at Capuchinos, in the Bay of Pasaia, and thus an archaeological heritage was lost which would surely have been amongst the most significant historical remains in Gipuzkoa.

Fishing and Fish-processing

Fishing played as important a part in the Roman economy as the production of cereal, wine and vegetable oil, with the population largely depending on it for their subsistence. Fresh or preserved, fish was served at practically every table in the empire; the wealthy sought out species they considered to be of high quality, but fish was also a staple diet of the poorer classes. Fish sauces were also common and are mentioned in the majority of contemporary recipes. At least four kinds of sauce are known garum, hallec, muria y liquamen. Of these, garum was the most popular. It was obtained by allowing the entrails of the fish to ferment naturally, using salt as an antiseptic agent to prevent putrefaction. Many kinds of fish, from large species like tuna to smaller fish were used. A mixture of one part salt to eight parts fish was left to dry in the sun for several weeks and stirred daily. Finally, the paste it was strained repeatedly until a clear sauce was obtained which was then stored in amphorae for transport and sale.

To meet this demand, fish factories developed for salting fish and making fish sauces all along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of Hispania, as well as the North African coast and the Atlantic coast of Gaul. Tuna was the most sought-after product, though smaller fish like sardines and mackerel were also processed. The factories were located close to the coast and a source of fresh water. They were made up of two basic spaces, one for cleaning and shredding the fish and the other containing the basins for macerating the produce with salt. For the factories to run smoothly there had to be both a supply of salt and a selective supply of fish.

The fish-processing plants on the Gipuzkoan coast shared these general features. One has been identified at Getaria, another at the Labourd port of Guethary, and it is very possible that between these two locations there were others, as yet undocumented. It seems likely that the names Getaria and Guethary are related to the Latin word cetaria, meaning a fish-processing plant. Some years ago a row of salting-basins was discovered at the railway station in Guethary and soon afterwards it was confirmed that Getaria in Gipuzkoa had also been occupied by the Romans. The first remains brought to light in 1997 was confined to the area around the parish church of San Salvador, but subsequent research has shown that Roman occupation extended throughout the old quarter of the town. The archaeological evidence has been backed by linguistic research by Joaquín Gorrochategui of the University of the Basque Country who proposes a common etymological root for Getaria and Guethary.

Hook and Line Fishing

Rods were made of long, tough, flexible cane, and the line, of linen thread or horsehair. The hook was fixed on the end of the line, baited, and weighted with lead. Cork floats were used to signal a catch, as they are today. Deepwater fishing was also practised with a setline, with several baited hooks around a central stock. The hooks (hamus) were made of iron, bronze or copper, depending on the size of the fish to be caught. Their shape has scarcely changed over the ages, as may be seen from the collections recovered from archaeological excavations in Gipuzkoa.

Nets

Amongst the nets most commonly employed was the so-called iaculum or funda, a small, funnel-shaped net with lead weights which was cast into the water from a height; the drag-net called sagena, verriculum or tragula, and the hand-net or hypoche. All these methods are known to have been used in this area because tools have been discovered that were used for making and repairing the nets. Such is the case of the shuttle, an implement comprising a narrow rod forked at both ends which was used to gather up the nets. The shuttle was moved alternately to the left and right over the weft to braid the net. Large, long-bodied, flat-headed needles with a hole in the head have also been unearthed, which would have been used for repairing and sewing the nets. Net-weights, too, have been found, consisting of pebbles with grooves for tying string onto, whose function was to keep the net submerged.

Fish Traps

These wicker or esparto cages were employed mainly in rivers and estuaries. They were designed in such a way that fish lured inside by the bait were unable to swim out again.

Weirs and Crab Nets

Weirs are constructions built on tidal flats and strands to trap fish at low tide. They are usually rounded in shape and make use of natural features, especially depressions. In Gipuzkoa there are a number of places where this type of fishing is practicable, as in Zumaia. In Getaria too, before extension work was completed on the harbour, it was common to see fish trapped in pools left on the uneven seabed at low tide.

There is also some archaeological evidence to suggest that crab nets may have been employed in this area in Roman times. A number of strips of lead have been found which are identical to those used today for weighing down the nets used for catching shellfish.

Spirituality

The Romans were in general tolerant of the religious practices of subject or colonised peoples. The only exceptions were their problems with the Jews and Druids, both of which undoubtedly had a political background, and later with the Christians, who were considered to be subversive of the established order. Only on one issue was compliance deemed compulsory – that of the cult of the emperor. Once this had been accepted there was room for the rites and traditions of other cultures, some of which made their way into the Roman pantheon. Many local gods could be identified with the figures of Mars or Jupiter, and could thus be associated with them in worship: thus we find MarsSutugi in Comminges and JupiterBesirisse in Cadéac.

Some deities travelled thousands of miles, as was the case of Mithras whose cult was spread by soldiers from its birthplace in the Middle East to the furthest corners of the empire, to become a socially important movement. Other gods, like the Celtic Deba and Arno, remained close to home. In practice the Romans had a wide-ranging pantheon with all kinds of major and minor gods covering practically the whole gamut of human activity. There was a god of war and of hunting, there were gods of rivers and fountains, gods for the protection of roads and navigation, a god of love, family gods who were worshipped at home, and so on. Daily life involved a constant relationship with divinities, and superstition and fetishism were endemic.

Image above: Goddess Isis (photograph at Oiassu Museum, G.Dijkman, August 2017)

This is the context to which the four idols found at Higer (Asturiaga-Hondarribia) belong. They appeared in the sand on the seabed alongside other articles indicating that they may have been part of a ritual hoard. They were accompanied by a jar of relatively sophisticated design, trays, and part of a lock, suggesting that all these items were originally held in a single container, perhaps a chest, and that they date from the middle of the second century. The idols, in the form of lamps, represent the goddess Minerva with a helmet and a breastplate on which appears the symbol of the Gorgon; the god Mars, bearded, with a breastplate and helmet; Helios, the sungod, with his crown of rays; and the goddess Isis with the symbol of the moon above her head.

The sun-god Helios also features on an oil-lamp recovered from the Roman mine of Arditurri III in Irun. The association between the symbol and the function of the lamp seems clear, especially if we bear in mind how dark the mines must have been. A figure of Minerva is also said to have been found in Renteria, but it has since disappeared, and there is no evidence at this time to attest its origin, or even that it comes from Gipuzkoa.

Other representations of gods from the ‘official’ pantheon include an image of the goddess Roma on the stone of a ring found during excavation of the Roman port at Tadeo Murgia St in Irun. The cameo or engraving is oval in shape and carved on a semi-precious stone. It is 13 millimetres in length and represents the divinity seated on her throne with all her symbols (helmet, shield, spear and victory scroll stretched over the palm of her left hand). The miniature is of very high quality, with very detailed carving showing the features and folds of the dress, the facial features of the figures and the details of the associated furniture in bold perspective.

We have already mentioned the Celtic deities of Deba and Arno as examples of the way native gods survived despite the spread of official cults. They may well have lived on in local place names too: it is quite possible that Arno Mountain and the nearby River Deba bear some relation to local cults. The cave of Santaili in Araotz, appears to derive not from St Elijah (Elias), but rather from St Ylia or Julia. She was in turn linked to the goddess Ivulvia, named on an inscription in Forua, in the Gernika estuary, who was associated with a cult of water worship. The small stone slab in Oltza at the foot of Aizkorri was probably used as an altar on ceremonial occasions.

Another well-documented feature of Roman spirituality were the funerary cults. The finest representation in this area is the necropolis of Santa Elena (St Helen) in Irun, but two epigraphs have also been found, one in Andrearriaga, described above, and the other at the foot of the altar of the chapel of St Peter in Zegama.

Image above: Eremita of Santa Elena (photograph, G.Dijkman, August 2017)

The Necropolis of Santa Elena

Excavations inside the chapel in 1971 revealed part of the cemetery of Oiasso. The find consisted of 106 urns containing the ashes of the deceased, most of whom were interred without any identifying features. Together with the urns, which also contained funerary hoards made up of objects like glass phials, hairpins, weapons and brooches, two stone constructions were discovered. One has a three-metre square base and has been identified as a cella memoriae or grave of importance. It contained the only glass urn found in the vicinity, indicating the high social rank of the deceased.

The other has a rectangular base five metres wide by seven and a half metres long and is a replica of the simple “in antis” temples. It includes a small porch adjoining the cella or principal chamber, as well as a roof of tegulae or rooftiles, whose remains were discovered amongst the rubble resulting from the collapse of the building after it fell into disuse in the fourth century. Cremation was not exclusive to the Romans, nor was it their only funerary tradition (they also buried their dead), but it was the general practice among Iron Age peoples. As Eastern beliefs were introduced and Christianity spread, however, it became less common and in time was completely replaced by burial.

Image above: Museum guide item number 166. Offerings are placed before the Roman tombstone at the foot of the altar in the chapel of San Pedro de Zegama to ward off headaches.

The tombstone at San Pedro de Zegama

The inscription is engraved on a slab of sandstone placed at the foot of the altar of the chapel. There are five lines of text giving the name of the deceased (LANICIVS, LATICIVS, LARICIVS or possibly L.ANNICIVS), his particulars and his age at death (forty), finishing in the funerary formula H(ic) e(st) or H(ic) i(acet). Above the text three arches are traced, symbolically depicting the gates of Hades or the House of the Dead. The stone dates from the end of the first or beginning of the second century A.D. and has been associated with Alavese inscriptions.

Christianity

During the fourth century Christianity ceased to be a proscribed and persecuted movement and became the religion of the emperors and later, the official religion of the empire itself. This new state of affairs brought about myriad changes in everyday life, as we can see from the items discovered from the period. A coin minted by the usurper Magnentius (350 – 355), found in Behobia, bears in the reverse the monogram of Christ and the Greek letters alpha and omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. These two letters were employed in the cryptic language of the early Christians to refer to the divinity of Christ, who was considered to be the beginning and end of all things.

On crockery too, the hitherto usual motifs of hunting scenes, pagan rituals and so on, were discarded in favour of Christian symbols such as crosses, monograms of Christ, palm-branches and others. Several examples of this pottery, “derived from Early Christian sigillata”, have been found in the Iruaxpe III cave in Aretxabaleta, which from their context appear to date from the fifth century. Others found at the Higer headland date from about the same time. Nonetheless, not all of Gipuzkoa abandoned paganism in favour of Christianity. In 1993 a number of cremation urns from around the eighth century were discovered inside the chapel of San Martin de Iraurgi in Azkoitia, clear evidence of the continuance of the old pagan funerary traditions.

Herding

Cattle, pigs and sheep are known to have been kept in this area since the Chalcolithic period, and herding was one of the most constant features of life in the late prehistoric period. It required that people follow the herds from place to place and until the castros were built, this nomadic society appears to have had no stable settlements. The people who built the dolmens and funeral mounds were probably wandering tribes ranging over a wide area in search of pasture and food for their livestock, their chief means of subsistence.

During the period of Roman occupation, the practice continued alongside the new urban society. Indeed it may well have become more widespread again during the late days of the Empire as a result of the crisis in the cities. The Romans looked down on all pastoral societies and mountain dwellers in general, reflecting attitudes they had inherited from the philosophical and ethnographical notions of their own distant past. They viewed such people as uncivilised, rough and uncouth, and did their best to avoid contact with them. Because they were not tied to fixed settlements, they were held to be uncontrollable and treated as little better than thieves and bandits.

Aside from these stereotypes, it is true that many of the inhabitants of Gipuzkoa, like those of other mountainous areas of the Empire, shared little in the high standards of living to be found in Oiasso. Living from herding, and continuing with their time-honoured traditions, they would have had few material goods that might encumber their mobility, their constant changes of dwelling-place and their adaptation to the precarious conditions of the environment. After the collapse of the structures which had sustained Roman order, they simply continued on their way. For those were dependant on the complex Roman organisations, however, even allowing for the transformations and gradual ruralisation of the later centuries, the transition must have been more difficult and painful.

Source

- texts: Oiassu Museum information & website: http://www.irun.org/oiasso/home.aspx?tabid=317

- Photographs by Oiassu Museum & G.Dijkman (August 2017)