Forua, Roman village & port (I-IV AD)

Below article is an impression of a visit to Forua Roman excavation site, a few kilometres north of Gernika, Basque Country, Spain, August 2017.

Original English summary of Spanish texts are those encountered on three displays at the north side of the dig. Unfortunately, the displays on the south of the excavations were missing. Photographs by G.Dijkman & Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide (2009). Original Spanish text follow below.

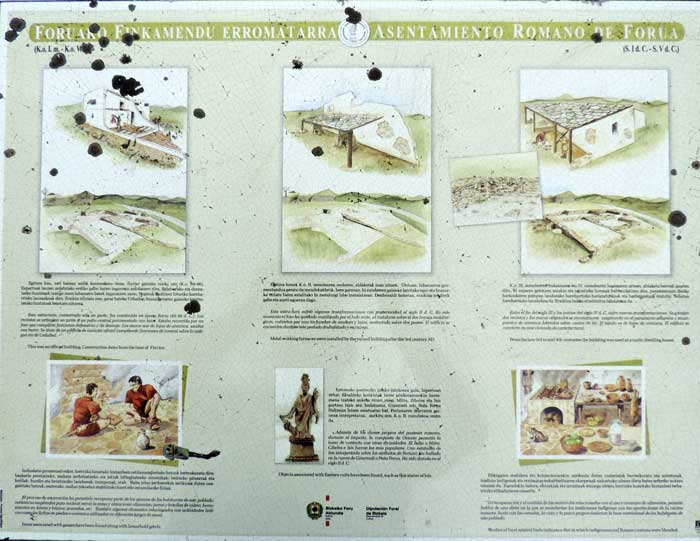

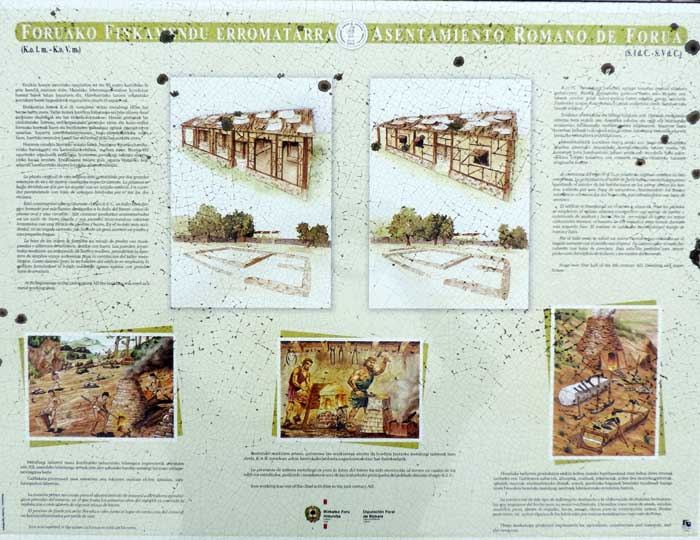

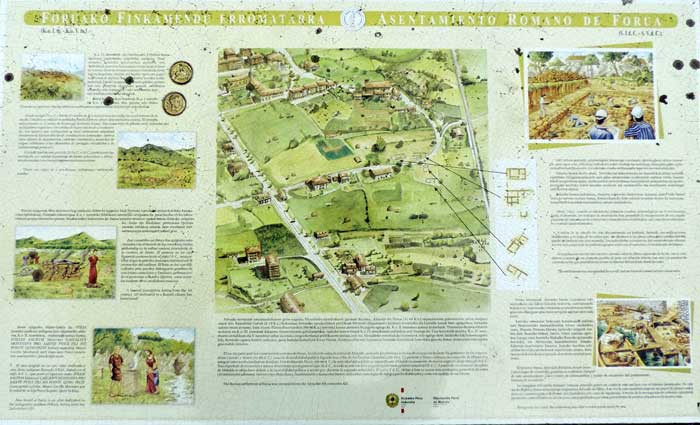

Images above: signs at the excavations (G.Dijkman, August 2017)

Forua: Port and Forum (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

The finest example of a Roman settlement in the province of Biscay is Forua. The settlement was founded between the years 41-68 A.D. as a forum and industrial site, where iron was worked, and also as a trading station and port. The archaeological remains retrieved during different excavations speaks of a population with Roman culture, in which new ways of cooking, eating or storing foods are evident (Terra Sigillata), where native customs co-exist alongside Roman tradition, as shown by the remains of containers made of ordinary ceramic.

Based on a study of the recovered archaeological materials, we can reconstruct certain aspects of everyday life in Biscay during the Roman period. Some have to do with the attire, as is the case of the footwear; fibulas or clasps used to fasten togas, the acus crinalis, to hold the hair in place, etc. Regarding the fabrics used for dressing, although no physical remains of fabrics have been found, there is evidence that linen and wool were used, as shown by the presence of weights and spindles that were used in looms. Others with the utensils and furniture used in the homes, such as light fixtures, lamps, keys, etc.

Roman settlement

It sprawled the higher part and the slope of the Elejalde Hill, extending over a surface of 60,000 m2. Ploughing activities in the last millennium and recent construction works have caused the disappearance of half of the original settlement. Nonetheless, the existence of housing construction, metallurgic workshops and storage facilities of the Roman village were preserved around the church of San Martín de Tours up until the tideland marsh.

The Roman settlement at Forua was occupied from the 1st to the 5th centuries AD.

The main nucleus of the Roman settlement of Forua, located on the Elejalde Hill, presents the first indication of occupation during the reign of emperors Claudius and Nero (41-68 AD), when the political stability was established after the end of the Cantabrian Wars (26-19 BC), allowing Rome to celebrate its conquest of Hispania and include these territories in its dominions. With the Flavian dynasty (69-96 AD), the activities of the settlement intensified, culminating in its zenith in the course of the II century AD.

After a transitional period of great dynamism during the III century AD, life in this enclave endured until the first half of the IV century AD. From this moment, the Elejalde Hill is deserted, due to political and social instability, which, in the second half of the IV and V century AD, forces the people to search for more protected areas to live. Under these adverse circumstances, caves such as Peña Forua, Santimamiñe and Lumentxa were used as a refuge by the inhabitants and as a hiding place for their goods.

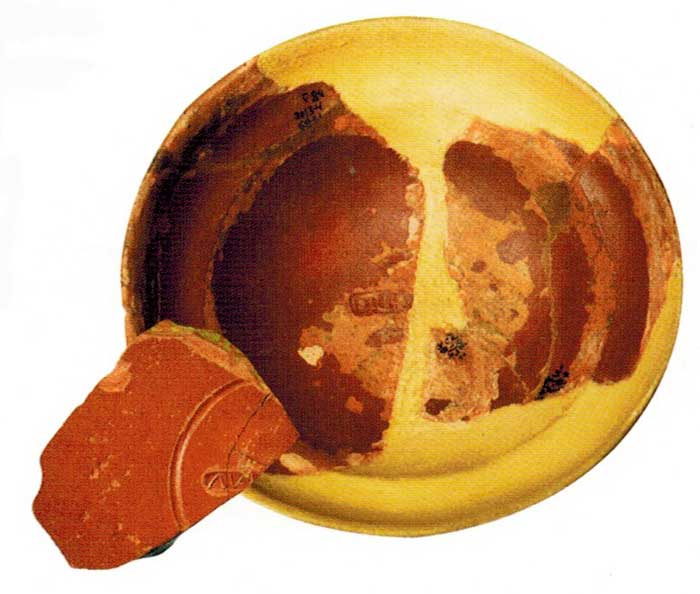

Image above: Pieces of pottery for dinner service of the Roman town of Forua. They are objects of Terra Sigillata Hispanica and Gallica, from the 1st to 2nd centuries A.D. The mark of the potter can be seen clearly (Sigillum). (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

The settlement was surrounded by a wall, but no trace of a street layout can be seen.

From 1982, in the initial stage of the archaeological surveys in the settlement, up to the present, excavation works have yielded a wide area of structures, consisting of living quarters and metallurgic workshops, and also an abundant, varied domestic dowry.

The study of this settlement has revealed a town, formed by constructions sprawling along the hillside, which, not coherent a pre-established urbanistic plan, is limited by a wall. The economic activities of the settlement consisted of a mixture of private usage of a town of agriculture and cattle raising, with commerce and iron metallurgy.

The location of this enclave, situated on the left bank of the Ría, with direct access by means of a small harbour, puts it in direct contact with this natural way of communication, by which contacts from the coast were established directly from the interior.

Being near the coast, the settlement was able to trade goods easily by sea.

The term Forua, from Latin ‘forum’ (market or commercial place), evidenced the role of this settlement as a central place of exchange and meeting place of this Roman village with its surroundings.

The complex terrestrial Roman road allowed contacts of this enclave with the interior of the peninsula. In this way, goods from the Ebro valley reached Forua. The maritime route, in turn, played a pivotal role for communication with the rest of Cantabria and the Aquitaine coast. By means of trade or traffic along the coast, it exported products such as iron or wool, exchanged for other goods from harbours along the same route.

Image above: excavations (G.Dijkman, August 2017)

Plate III: I-V century AD

This was an official building. Construction dates from the time of Flavius.

This structure, salvaged only in part, was constructed during the Flavian era (69-96 AD). The enclosures surround a central patio paved with (sandstone) slabs. It was circuited by a moat for its defence and drainage. The walls were made of sandstone slabs, united with mud. It was an official building, controlling the antique river Ría of Urdaibai.

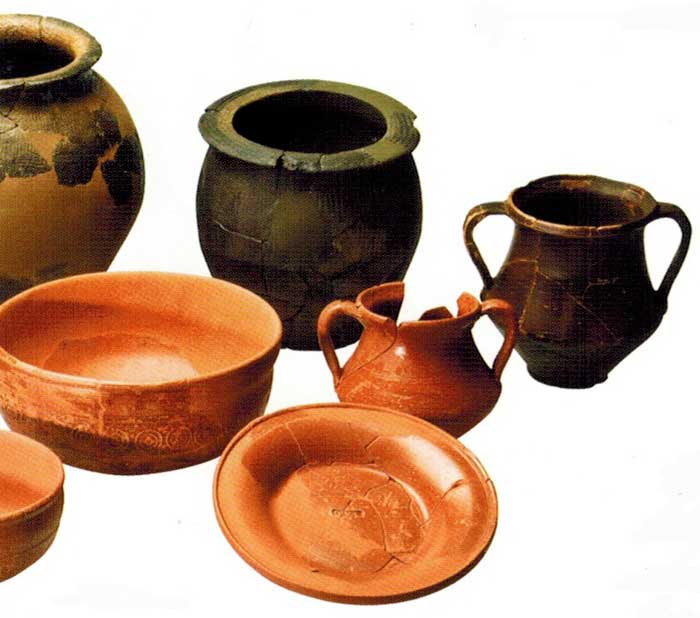

Image above: Kitchen and table objects from the Roman town of Forua and Ereñuko Arizti cave. Terra Sigillata Hispanica and common pottery. 1st to 4th centuries A.D. They are objects for daily use, in which the indigenous tradition is once again mixed with aesthetic innovations from the Roman world. (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

Items associated with games have been found along with household goods.

The excavation process partly enabled the recuperation of the furnishings of the inhabitants of this settlement: ceramics used for cooking, to serve at tables and stock food items; jars and glass; iron and bronze tools; coins, etc.; and also items related to games such as stone and ceramic chips used for various table games.

Image above: Metal material from the Roman town of Forua. A locally manufactured axe and iron block. 1st-2nd centuries A.D. (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

Metal working furnaces were installed by the ruined building after the 3rd century AD.

This structure underwent a number of transformations well into the second century AD. At this stage, the moat on the west side was no longer used when two metallurgic furnaces were built on top, covered with a roof of wood and (sandstone?) slabs, supported by two points of fixture. During this period, the building was deserted, and is now in ruins.

Objects associated with Eastern cults have been found, such as this statue of Isis.

Apart from their own gods belonging to the Roman pantheon during this Imperial period, the conquest of the East enabled contacts with other divinities. The cult of Mitra, Cibeles and Isis were the most popular. A statue of Isis, interpreted as one of the attributes of Fortuna, was found in the Cave of Ginerradi or Peña Forua. It dates back to the second century AD.

Image above: Isis-Fortune statue. Peña Forua cave (Forua). 1st to 2nd centuries A.D.; A significant piece that shows the religious syncretism of the Roman world (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

From the late 3rd to mid 4th centuries, the building was used as rustic dwelling house.

Between the end of the third and beginnings of the fourth century AD, it underwent other transformations. Two additional enclosures were added and the original walls were reconstructed, using the ashlar vestments and rough sandstone walls carved on river edges. The roof consists of sandstone slabs. The building is converted into a rural housing.

Studies of food-related finds indicate a diet in which indigenous and Roman customs were blended.

The retrieval and the analysis of the materials in connection to the use of food items supports the idea of a diet in which the indigenous traditions were mixed with imported Roman cuisine. Together with cereals, items of wild hunt and fishery constituted the basic nutritional elements of the inhabitants of this settlement.

Plate I: I-V century AD

At its beginnings in the 2nd century AD the building was used as a metal workshop.

The original floor of this building consists of two large rooms of respectively 44 by 60 square metres. The first contains two spaces, divided by a small wall with a broad threshold. A paved corridor with sandstone slabs bordered the two areas on the south.

In the second century AD, this construction housed a metallurgic workshop, consisting of six furnaces to forge iron, five oval floors and one circular floor. Its rooms were found half underground in treaded soil, and the trunk-formed walls were raised by a mixture of stones and mud. In the area most to the east, in the southeaster corner, a large stone mortar was found, and a small forge.

The base of the walls consisted of a stone socle with walls made of stone and sandstone ashlars, united with mud. The walls, raised by a framework of mud and wood, gave way to wide openings for air ventilation in the metallurgic workshop. For the roof of the building, wood was used, attached to large sandstone slabs.

Iron was melted at the mines in furnaces with air blowers.

The first material necessary for the supply of minerals for the metallurgic workshops came from the surrounding areas, which up until the first years of the twentieth century was known as the open-air exploitation of some iron mines. The process of iron melting or casting was realised in the same place as the mineral extraction, in furnaces of air bellows.

Iron working was one of the chief activities in the second century AD.

The presence of metallurgic workshops for the working of iron has been encountered in at least four of the researched buildings, and was considered one of the principle activities of the population during the second century AD.

Stage two: first half of the 4th century AD. Dwelling and storehouse.

At the beginning of the IV century AD, a number of changes to this structure were made. The activities in the furnace workshop had ceased some time earlier, leaving the interior of the rooms, where the furnaces were opened, covered with a layer of rubble. Keeping the initial boundaries intact, the two rooms were reformed with a pavement of sandstone slabs.

The building is transformed into housing and storage area. The same construction system was applied to the walls, using a stone socle and a framework of wood and mud. In this second phase, to realise thermic insulation, the windows were reduced in size. To cover the construction, the use of a roof of branches and (stone) slabs was continued.

On the west side, in the southwest corner, a new corridor was created adjacent to the original south corridor. In both corridors, the floor was covered with sandstone slabs. This solution offered the building more protection from the rains and northwest winds.

Image above: Different pottery, bone and metal objects, of daily use retrieved in the Roman town of Forua: bronze key, acus crinalis, game counters, sandal sole (caligae). (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

These workshops produced implements for agriculture, construction and transport and also weapons.

The production of this type of workshops was aimed at the various tools, which required iron for the best yield. Utensils such as ploughing grilles, hoes, hammers, pickaxes, shearing scissors, sickles, churning instruments, nails for construction, weapons, vehicle tyres, etc. were some of the products made in metallurgic workshops such as this one in Forua.

Image above: Forua excavations (G.Dijkman, August 2017)

Plate II: I-V century AD

There are signs of a pre-Roman indigenous settlement nearby.

From the VI century BC until the change of the millennium, the indigenous settlement around Ría de Urdaibai was constructed, and high, fortified settlements, potent castros, were constructed. The nearest example is the castro of Kosnoaga (Gernika-Lumo). The houses there had an oval-shaped floor, covered with roofs made of plant material, decorated with kneaded and hardened mud. The furnishings of these constructions show elements of local fabrication - not turned ceramics - together with other imported objects, such as ceramics and coins of Celtiberian origin or status elements linked to personal clothing. In the last phase of this period (I century BC - I century AD), necropoles were discovered with funerary steles of prismatic or disc-shaped form with crosses and solar representations.

A funeral inscription dating from the first century AD dedicated to a Roman citizen has been found.

In Forua, two epigraphs have been found, pertaining to the religious realm: both of these were processed in limestone rose windows (motif?) from the Ereño quarry. The first is a funerary ‘cippus’ that belongs to the I century AD, when the habitual funerary process consisted of the cremation of the corpse. The text is hard to read, but certain names of Latin origin are distinguished, such as Iunio and Emiliano, belonging to the tribus Quirina, clear proof of their Roman citizenship.

Image above: Altar stone, made of Ereño's marble, Roman town of Forua. 1st-2nd centuries A.D. Consecrated by a Roman citizen to the indigenous divinity Ivilia. (Bilbao Archaeology Museum Guide, 2009)

Also found at Forua is an altar dedicated to the indigenous goddess IVLIA, dating from the 2nd century AD.

The other epigraph is an altar dedicated to an indigenous goddess called IVLIA, dating back to the II century AD, with the following test: IULIAE SACRUM M(arcus) CAECILIUS MONTANUS PRO SALUTE FUSCI FILI SUI PROSUIT, QUNO FECIT. Consecrated to Iulia. Marco Cecilio Montano for the health of his son, Fusco named him. Made by Quno.

Image above: Forua excavations, area not documented, southern side (G.Dijkman, August 2017)

Source

- text: displays at the Roman excavation site of Forua (translation from Spanish into English by G.Dijkman)

- text: http://www.forua.net/es-ES/Turismo/Patrimonio-Historico-Cultural/Paginas/default.aspx

- Candina, Begoña (2009) - Roots of a People, Arkeologi Museoa's Guides, Permanent Exhibition, pp.44-50, ISBN 978-84-7752-480-9

- photographs by G.Dijkman (August 2017)

Original Spanish text

Poblado Romano

Ocupó la parte alta y las laderas de la colina de Elejalde, hasta extenderse por una superficie de 60.000 m2. Los trabajos de roturación a lo largo del último milenio y las construcciones recientes han contribuido a la desaparición de la mitad del yacimiento original. Aún así, hemos constatado la existencia de estructuras de habitación, talleres metalúrgicos y almacenes del poblado romano desde el entorno de la iglesia de San Martín de Tours hasta la marisma.

El núcleo principal del asentamiento romano de Forua, localizado sobre la colina de Elejalde, presenta los primeros indicios de ocupación durante los gobiernos de los emperadores Claudio y Nerón (41-68 d.C.), cuando la estabilidad política lograda tras la fin de las Guerras Cántabras (26-19 a.C.) permite a Roma culminar la conquista de Hispania e integrar estos territorios bajo su dominio. Con la dinastía Flavia (69-96 d.C.) la actividad del poblado se intensificará, viviendo su momento de mayor auge a lo largo del siglo II d.C. Tras el período de transición y menor dinamismo que supone el siglo III d.C., la vida en este enclave se prolongará hasta primera mitad del IV d.C. A partir de ese momento la colina de Elejalde se abandona debido a la inestabilidad político y social que, durante la segunda mitad del s. IV y el s. V d.C., obliga a buscar zonas más protegidas para vivir. En estas circunstancias adversas, cuevas como Peña Forua, Santimamiñe o Lumentxa fueron utilizadas como lugar de refugio por los habitantes y como escondrijo de sus bienes.

Desde 1982, cuando se inician los primeros sondeos arqueológicas en el yacimiento hasta el presente, los trabajos de excavación han permitido la recuperación de un amplio conjunto de estructuras de habitación y manufactura metalúrgica, así como de un abundante y variado ajuar doméstico. A través de su estudio ha sido documentado un poblado, formado por edicicaciones distribuidas a lo largo de la colina que, sin obedecer a un plano urbanístico preestablecido queda delimitado por una muralla. Las actividades económicas del asentamiento alternaron los usos propios du un poblado agropecuario con el comercio y la metalurgia del hierro. El emplazamiento de este enclave, situado sobre la ribera izquierda de la ría, con acceso directo a través de un pequeño puerto, lo pone en relación directa con esta vía natural de comunicación que permitiría el acceso al interior del territorio desde la costa.

El término Forua, derivado del latino fórum (mercado o lugar de comercio), pondría en evidencia el papel de este asentamiento como centro de intercambios y punto de encuentro del poblamiento romano de su entorno. La compleja red viaria terrestre romana permitió poner en contacto este enclave con el interior peninsular. De este modo llegan a Forua mercancías originarias del valle del Ebro. A su vez la ruta marítima jugaría un papel de primer orden para su comunicación con el resto del Cantábrico y la costa de Aquitania. A través del la navegación de cabotaje exportaría productos como el hierro local o la lana, intercambiados por otros procedentes de puertos situados en la misma ruta.

Esta estructura, conservada sólo en parte, fue construida en época Flavia (69-96 d.C.). Los recintos se articulan en torno a un patio central pavimentado con lajas. Estaba recorrida por un foso que cumpliría funciones defensivas y de drenaje. Los muros son de lajas de arenisca, unidas con barro. Se trata de un edificio de carácter oficial cumpliendo funciones de control sobre la antigua ría de Urdaibai.

El proceso de excavación ha permitido recuperar parte de los ajuares de los habitantes de este poblado: cerámicas empleadas para cocinar; servir la mesa y almacenar alimentos; jarras y botellas de vidrio; herramientas en hierro y bronce; monedas, etc. También algunos elementos relacionados con actividades lúdicas como las fichas en piedra o cerámica utilizadas en diferentes juegos de mesa.

Esta estructura sufrió algunas transformaciones con posterioridad al siglo II d.C. En este momento el foso ha quedado inutilizado por el lado oeste, al instalarse sobre él dos hornos metalúrgicos, cubiertos por una techumbre de madera y lajas, sustentada sobre dos postres: El edificio se encuentra durante este periodo deshabitado y en ruinas.

Además de los dioses propios del panteón romano, durante el Imperio, la conquista de Oriente permitió la toma de contacto con otras divinidades. El culto a Mitra, Cibeles e Isis fueron los más populares. Una estatua de Isis interpretada sobre los atributos de Fortuna fue hallada en la cueva de Ginerradi o Peña Forua. Ha sido datada en el siglo II .d.C.

Entre el fin del siglo III y los inicios del siglo IV d.C. sufre nuevas transformaciones. Se añaden dos recintos y los muros originales se reconstruyen empleando el paramento sillarejos y mampuestos de arenisca labrados sobre cantos de río. El tejado es de lajas de arenisca. El edificio se convierte en una vivienda de carácter rural.

La recuperación y el análisis de los materiales relacionados con le uso y consumo de alimentos, permite hablar de una dieta en la que se mezclarían las tradiciones indígenas con las aportaciones de la cocina romana. Junto con los cereales, la caza y la pesca proporcionarían la base nutricional de los habitantes de este poblado.

La planta original de este edificio está constituido por dos grandes estancias de 44 y 60 metros cuadrados respectivamente. La primera se halla dividida en dos por un murete con un amplio umbral. Un corredor pavimentado con lajas de arenisca bordeaba por el sur los dos recintos.

Esta construcción albergó durante el siglo II d.C. un taller metalúrgico formado por seis hornos destinados a la forja del hierro, cinco de planta oval y una circular. Sus cámaras quedarían semienterradas en un suelo de tierra pisada y sus paredes troncocónicas estarían levantadas con una mezcla de piedras y barro. En el recinto más occidental, en su ángulo suroeste, fue hallado un gran mortero en piedra y una pequeña fragua.

La base de los muros la formaba un zócalo de piedra con mampuestos y sillarejos de arenisca, unidos con barro. Las paredes, levantadas mediante un entramado de barro y madera, permitirían la apertura de amplios vanos necesarios para la ventilación del taller metalúrgico. Como sistema para la techumbre del edificio se emplearía la madera formándose el tejado mediante sujetas con grandes lajas de arenisca.

La materia prima necesaria para el abastecimiento de mineral a los talleres metalúrgicos procedía del entorno, en el que hasta los primeros años del siglo XX es conocida la explotación a cielo abierto de algunas minas de hierro. El proceso de fundición sería llevado a cabo junto al lugar de extracción del mineral, en hornos alimentados por fuelle de aire.

La presencia de talleres metalúrgicos para la labra del hierro ha sido reconocida al menos en cuatro de los edificios estudiados, pidiendo considerarse una de las actividades principales del poblado durante el siglo II d.C.

A comienzos del siglo IV d.C. se producen algunos cambios en esta estructura. La actividad en el taller de forja había cesado tiempo atrás quedando el interior de las habitaciones en las que se abrían los hornos, cubierto por una capa de escombros. Manteniendo los límites iniciales se reforman las dos estancias, pavimentándolas con lajas de arenisca.

El edificio se transforma en vivienda y almacén. Para las paredes se emplearía el mismo sistema constructivo con zócalo de piedra y entramado de madera y barro. Por la necesidad de lograr un mejor aislamiento térmico, el tamaño de las ventanas sería menor, durante esta segunda fase. El sistema de cubrición mantendría el tejado de ramas y lajas.

Por el lado oeste se adosó un nuevo corredor que enlazaba en el ángulo suroeste con el pasillo sur original. En ambos casos el suelo fue cubierto con lajas de arenisca. Esta solución permitía una mayor protección del edificio de la lluvia y los vientos des noroeste.

La producción de este tipo de talleres iría destinada a la elaboración de distintas herramientas que requieren del hierro para su mejor rendimiento. Utensilios como rejas de arado, azadas, martillos, picos, tijeras de esquilar; hoces, mazas, clavos para la construcción, armas, llantas para carro, etc. serían algunos de los fabricados por centros metalúrgicos como este de Forua.

Desde el siglo VI a.C. y hasta el cambio de Era el poblamiento indígena en el entorno de la ría de Urdaibai se realizó en poblados fortificados en altura denominados castros. El ejemplo más próximo es el castro de Kosnoaga (Gernika-Lumo). Sus casas eran de planta oval, cubiertas por techumbres vegetales y revestidas de barro amasado y endurecido. Los ajuares que acompañan a estas estructuras muestran elementos de fabricación local - cerámicas no torneadas - junto a otros objetos de importación, como las cerámicas y monedas de origen celtibérico o los elementos de prestigio vinculados a la indumentaria personal. A la fase final de este periodo (S.I.a.C - I.d.C.) pertenecen las necrópolis con estelas funerarias de forma prismática o discoidea decoradas con cruces y representaciones solares.

Son conocidos en Forua dos epígrafes relacionados con el mundo des las creencias: ambos elaborados en la caliza rosácea procedente de la cantera de Ereño. El primero es un cipo funerario perteciniente al siglo I d.C., momento en el que la práctica funeraria habitual era la cremación del cadáver. El texto se lee con dificultades pero pueden distinguirse nombres de raíz latina como Iunio y Emiliano, perteneciendo el personaje a la tribu Quirina, como muestra evidente de su ciudadanía romana.

El otro epígrafe es un ara, altar dedicado a una diosa indígena llamada IVLIA, datada en el siglo II d.C., que porta el siguiente texto: IULIAE SACRUM M(arcus) CAECILIUS MONTANUS PRO SALUTE FUSCI FILI SUI PROSUIT, QUNO FECIT. Consagrada a Iulia. Marco Cecilio Montano por la salud de su hijo Fusco la puso. Quno la hizo.